Jump to the content

- {{#headlines}}

- {{title}} {{/headlines}}

Margaret E. Roberts

Professor Dr Margaret E. Roberts teaches and conducts research at the Department of Political Science and the Halıcıoğlu Data Science Institute at the University of California, San Diego, United States. There, she is also co-director of the China Data Lab at the 21st Century China Center. Her book “Censored: Distraction and Diversion Inside China’s Great Firewall” (Princeton University Press, 2018) received multiple awards. In 2022, she was granted the Max Planck-Humboldt Research Award, a joint award by the Humboldt Foundation and the Max Planck Society valued at 1.5 million euros.

The fact that Margaret E. Roberts is currently researching into censorship and the influence of social media platforms on people’s decisionmaking is due to a coincidence. Or rather, a discovery the American made quite by chance.

When Roberts, known as Molly, began working on her doctorate at Harvard in 2009, she actually intended to focus on international trade relations. She had previously studied international relations and economics at Stanford and received a Master’s in statistics there. She had, moreover, taken Chinese language classes and repeatedly spent time in China. “I was very interested in the rapid growth of the Chinese economy at that time and wanted to use data analysis to discover how it came about,” says Roberts. But everything turned out differently.

AI recognises patterns in texts that humans often don’t discover.

Molly Roberts’ supervisor at Harvard was Gary King, a world-leading specialist in quantitative methods. “Gary wrote to tell me and another graduate student at Harvard, Jennifer Pan, that he had found all these Chinese blogs and there were far too many of them to read them all,” Roberts explains in a video chat from her apartment in California, where she lives with her husband and children. “He wanted to know whether I would be interested in finding out how you could use artificial intelligence to discover a way of structuring this mass of data.”

Criticism disappears from the web

The blog posts King had downloaded from the Chinese Internet were all about workers’ protests. Roberts was supposed to ascertain whether the texts were positive or negative. To do so, she initially had to train the artificial intelligence. “The first thing we did was to assign numbers to frequently used terms,” Roberts explains. “Then we read the texts, evaluated them and labelled them: here someone is writing something positive about the protest, there it’s being portrayed negatively.” On the basis of these examples, the computer learned to interpret words and word contexts according to the instructions. “The fascinating thing about AI is that it can recognise patterns on a deeper level that we humans often can’t access.” In this respect, according to Roberts, the machine is ahead of the human brain.

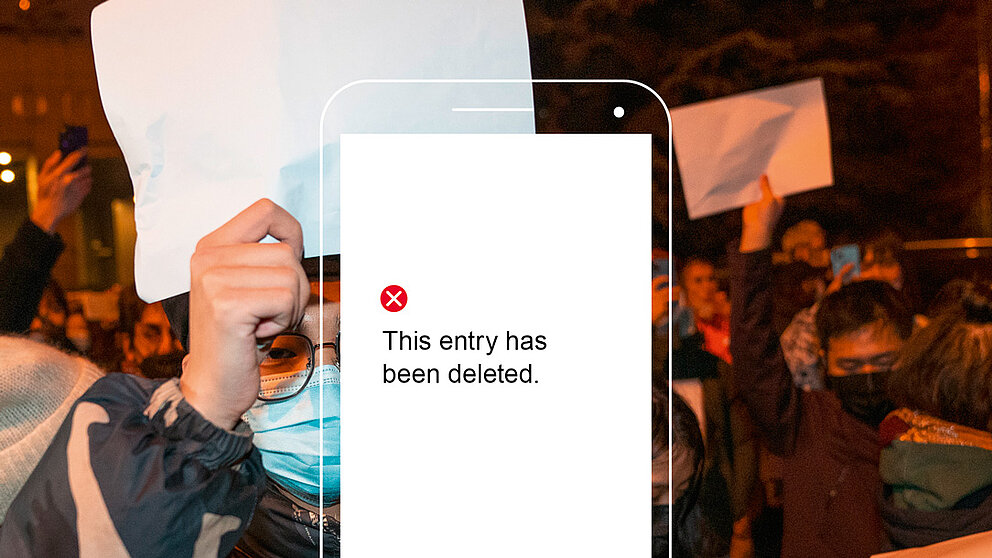

Six months into her work, Roberts and her collaborators noticed something. Because the evaluation of one of the blog posts was not completely clear, she typed in the URL to search for additional information on the original page. But the post wasn’t there anymore. “Sorry, this entry is no longer available” appeared on her screen. The researcher started checking other URLs and discovered that especially the posts that had been positive about the protests had disappeared. It soon became clear that the Chinese Propaganda Ministry must have censored the posts. Roberts realised what she had hit on: “Without searching for it, we had found a mechanism for measuring Internet censorship,” she says, still sounding really excited when she talks about it.

Roberts wrote a programme that regularly pinged the pages to see whether they were still online. No easy task. If the computer pings too often, at some stage the sender, i.e., the computer, will be blocked. “I first had to learn quite a lot about programming,” says Roberts, laughing. And she managed that, too. But it also meant that she had to decide what she wanted to work on in the future: international trade relations or censorship?

Local protests are the most provocative

“I woke up in the morning and the first thing I thought about was censorship,” says Roberts. That’s when she knew she had to change her plans.” In 2013, together with Gary King and Jennifer Pan, she published a paper in the American Political Science Review, describing how the Chinese government, whilst allowing criticism, nonetheless severely restricted the population’s collective expression. She completed her doctorate on the subject a year later.

“It’s reports about local protests that are subject to most censorship in China,” says Roberts, summarising her main findings at the time: when people go onto the streets to protest about expropriation, for example, or police brutality. Roberts was able to follow live how posts on such topics disappeared from blogs and forums. “We often think censorship functions via punishment, when people are imprisoned, for instance, because of something that they have written,” she says. That is certainly true, she states, not just in China but in other authoritarian states like Russia and Iran, too. But in all these countries you can also observe what a major role access to information plays.

Information becomes harder to access without people noticing.

In Russia, the government purposely spreads misinformation to cover up what is really happening in the war in Ukraine. In Iran, the regime throttles the Internet in the hope of preventing protesters from connecting and preventing information from getting out. But censorship, according to Roberts, is more than that. Particularly in peacetime, censorship is often far more subtle.

“Certain kinds of information become harder to access without people necessarily noticing,” she explains. “They have to make much more of an effort to get at the information, but many people don’t make the effort because it’s often just not practical in everyday life.” Take local protests in China, for example: “Let’s assume a person has heard about a protest but can’t find anything about it online because all the posts on the topic have been tacitly removed,” Roberts explains. “This person will ask themselves: Are there any protests happening at all? Or perhaps they will think: It can’t be that important, after all.”

Protests remain hidden

In this situation, people need to have observed the protests themselves or heard about them from others if they are to find out about them in the first place. And in order to access blocked foreign media and their reporting, you need technical solutions like virtual private network (VPN) connections to bypass the censor. But that costs money and involves a good deal of effort, so not everyone will go the extra mile. Consequently, says Roberts, networking directed against the government and the narrative it pursues is forestalled or at least made more difficult.

Roberts is now a professor at the University of California in San Diego where she teaches and conducts research. In 2022, she received the Max Planck-Humboldt Research Award, which is granted jointly by the Humboldt Foundation and the Max Planck Society. The selection committee was convinced by Roberts’ unusual career and innovative research profile. She wants to use the award amount of 1.5 million euros to extend her research on censorship and launch a project on the role of social media platforms together with the Technical University of Munich and the University of Konstanz.

Asked about her career path, Molly Roberts says she was very lucky – simply because she had the opportunity to freely pursue her ideas and interests. “It was just on a whim that I signed up for Chinese language classes when I was a student.” She had never even been to Asia when she started university. “I was just curious and wanted to try something new.” Again, it was a mentor who nudged her in the right direction. “She recommended me to take an extra course in sociology that dealt with China under Mao.” After the course, Roberts was so fascinated that, in 2005, she spontaneously applied to a programme enabling her to spend the summer in China. It would be the first of many visits there and she spent one semester studying in Beijing. “One of the things that has always fascinated me about China is the speed of economic development,” says Roberts. “Every time you go there, everything looks completely different because so much has happened.”

Roberts got involved in artificial intelligence through statistics. For her final project on a machine learning course at Harvard, she developed a digital tool for topic analysis that she still uses to this day. “The analysis examines the words in the various documents and then calculates which topics are the most probable,” Roberts explains. In this way huge datasets can be evaluated with the help of a computer. Together with a fellow student, Brandon Stewart, Roberts wrote a programme which also allows you to trace how topics change in the course of time. For evaluating social media platforms, this is now worth its weight in gold because you can follow online debates using the programme without having to read every single post.

According to Roberts, the fascinating thing about it is that the machine more or less does it unsupervised. This means that now, unlike in her earlier research on Chinese blog posts, neither the topics nor the valuations are determined in advance. “The tool does the filtering on its own using word probability distribution,” says Roberts. “I only interpret which topic the terms belong to afterwards.” The programme is now also used by other researchers as well as journalists for evaluating social media posts.

The censor as moderator

Thanks to receiving the Max Planck-Humboldt Research Award, Roberts now wants to channel these diverse findings into a completely new project: she intends to investigate how users are influenced on social media platforms and analyse their content moderation methods, which are anything but transparent. Molly Roberts will cooperate, amongst others, with the Konstanz political scientist Nils B. Weidmann, who conducts research on protest movements and civil wars as well as digital communication and political mobilisation. Weidmann originally came to Konstanz sponsored by the Humboldt Foundation: in 2012, he relocated there from Norway on the strength of a Sofja Kovalevskaja Award and used the funding for outstanding junior researchers to build up his own research project and working groups.

“The emergence of social media platforms has produced a raft of new, interesting phenomena,” says Roberts and lists just some of them: disinformation, online harassment, hate speech, the influence of foreign governments on elections. She now wants to explore the tools that are necessary to guarantee freedom of information as well as the influence that internal moderation methods on social media platforms have on democracies. Her project is scheduled to take five years, and Roberts intends to commute between California and Germany.

Most of the work is done at the computer anyway, she notes. And the tools that she developed in the past will stand her in good stead here as well. “We’re talking huge volumes of data,” says Roberts. “They can only be tackled with the help of artificial intelligence and machine learning.”