Jump to the content

- {{#headlines}}

- {{title}} {{/headlines}}

Born in 1972 in New Delhi, Andrea Wulf grew up in Hamburg. She studied Cultural Science and History of Design in Lüneburg and London where she has lived ever since. She works as an author, has published six books and written for numerous newspapers.

Andrea Wulf, you recently accompanied German Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier on a six-day journey tracing the footsteps of Alexander von Humboldt. Starting in Berlin, you visited Cartagena, Bogotá, Quito, the Galapagos Islands and Guayaquil before flying back to Berlin. That sounds quite hectic...

Yes indeed, those six days were incredibly busy. I felt like I was constantly on the go, just like Humboldt. But it was a great experience. Eight years ago, I was sitting in the archives doing my research on Humboldt. If someone had told me then that, in 2019, I would be in Quito listening to the President of Germany delivering a long speech highlighting the role of Humboldt in the current debate on climate change, I would never have believed them. That was a ‘goose-bump moment’ for me.

How long would your itinerary have taken Humboldt?

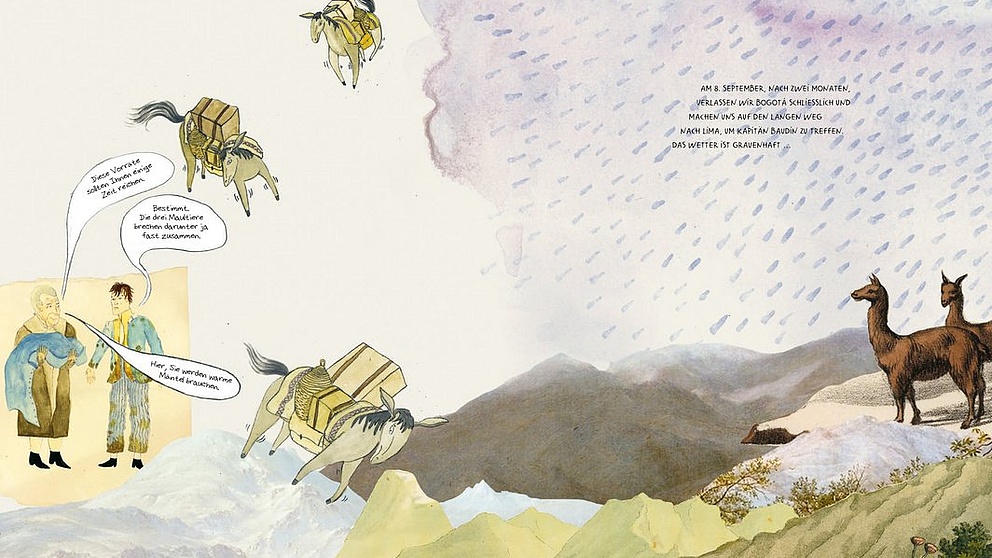

Probably years. He actually went everywhere on foot. Our flight from Cartagena to Bogotá took just an hour. This stage of the journey alone took Humboldt almost four months.

Can one begin to imagine what it must have been like for Humboldt travelling in those days?

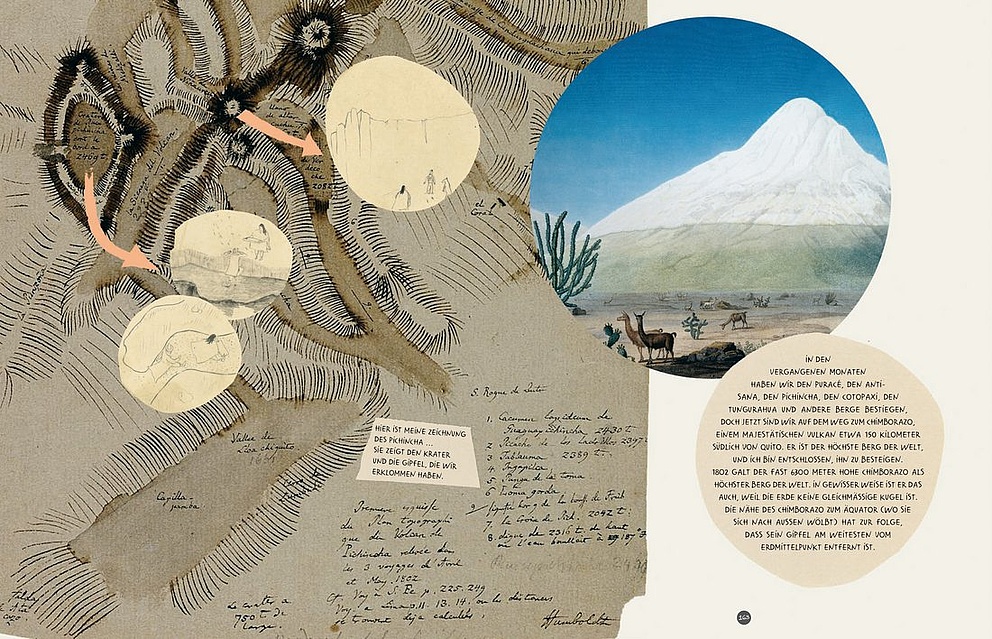

Difficult, but just about. Like Humboldt, I walked up to the top of the Chimborazo volcano in Ecuador, but I was wearing good shoes and carrying modern equipment. But I didn’t even climb as far as he did. I only got to about 5,000 metres, and that was utterly exhausting. In 1802, Humboldt climbed nearly 6,000 metres wearing canvas trousers and tattered shoes and with bleeding feet. It must have been incredibly tough going.

What were you looking for on Chimborazo, the highest known peak in Humboldt’s time at 6,267 metres?

This ascent was important to me, because up there on Chimborazo, Humboldt had a flash of enlightenment that became central to his understanding of nature.

In your new book, The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt, you maintain that Humboldt had an inspiration up there on the volcano, which formed his ‘holistic’ concept of nature, as we might describe it today.

Yes exactly. He thought he was standing on the highest point of the earth, and from up there he conceived of nature as one immense and coherent whole. He realised that the trek from Quito almost to the summit of Chimborazo was like a botanical journey from the equator through all the climate zones to the North Pole. He observed the extent to which the plants – from the tropical trees in the valleys to the last vestiges of lichen on the snow line – resembled other plants from other corners of the world. It became clear to him that there are global vegetation zones; from then on, he no longer sought to shoehorn the plant world into a rigid classification system like other scientists but instead made cross-connections.

In your book, you also mention an expedition in 2012 which found that the plants on Chimborazo have since spread 500 metres further up – evidence for climate change. Is Humboldt the forerunner of modern environmentalism for you?

Yes, he is the forgotten father of environmentalism. In his speech in Quito, Steinmeier called him the ‘Father of Ecology’. Humboldt was of course unfamiliar with the term ‘ecology’, because it was only coined later. But he constantly refers to nature as a living organism threatened by man. Time and again, he describes how humans are destroying nature and the consequences of artificial irrigation, deforestation and the like. When he sees how the valleys around Mexico City are withering and dying, he writes: “I think that they set out to violate nature.” He was warning about climate change even back then. He was certainly a pioneer of environmentalism, but let’s be honest, he never turned to activism.

For this new book, you’ve embarked on a very special journey: you’ve worked your way through Humboldt’s diaries – more than 4,000 pages. Which of the various Humboldts did you find on your journey?

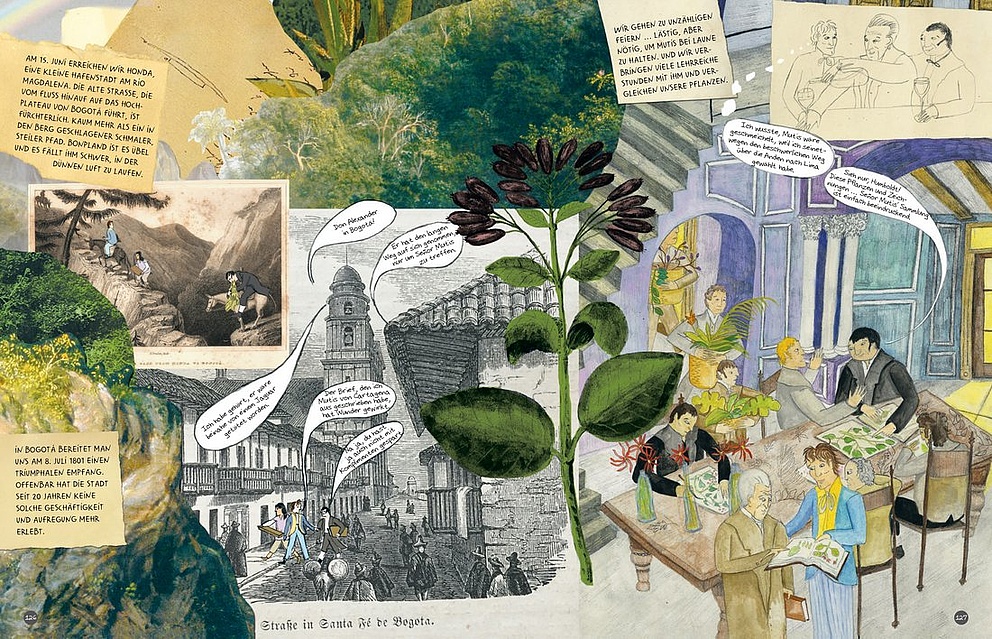

It was already possible to read transcripts of the diaries, but since the first pages started to appear online in 2014, they can now be viewed in the original – handwritten and with his drawings. It is apparent that Humboldt had a very strong artistic side, and that’s the reason why I wanted to publish The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt as an illustrated book. He is often seen as this empiricist who roamed around South America with a set of 42 measuring instruments. But that is completely wrong. Humboldt was a person who kept saying we have to use our imagination and our feeling to understand nature. That is plain to see from his diaries: hundreds of sketches, animals, plants, calculations, silhouettes of volcanoes, maps. These are never simple passages of prose – Humboldt was constantly sticking new scraps of paper on top and adding sketches. These are multi-layered collages of his observations and thoughts. A testimony to a restless spirit which was constantly coming up with new ideas and never thinking in linear fashion but always in multiple directions all at the same time.

In your book, you allow Humboldt to recount not only his research and his discoveries but also his everyday experiences. On one occasion, he and his companion, the botanist Bonpland, adopt a stray dog. Were you making the point that Humboldt was also just a human being?

Yes, absolutely. It was not conceived as an academic study but rather as a book for a general audience. The research is of academic standard, because I used only primary sources. But it is very important to me that it not only depicts Humboldt as a scientist but also as a human being, because I believe that the one cannot exist without the other – they cannot be separated. Human nature determines the approach to science that the individual will take. Humboldt’s character was such that he wanted to go on expeditions. And if he hadn’t gone, he would have become a completely different sort of scientist.

We can’t talk about the human side to Humboldt without mentioning his sexuality. You explicitly address Humboldt’s presumed homosexuality, but the only words you put into his mouth are: “I never had a wife because I was always too busy for a family.”

We cannot say any more than that, because nothing more is known. Anything else would be poetic licence; it is very important to me that I do not make anything up in my books. Personally, I am 99.9 percent sure that Humboldt was gay. But what nobody knows for sure, as there is no supporting documentary evidence, is whether Humboldt was a practising homosexual. What we can say with certainty, however, is that he never had a relationship with a woman, because if the most famous scientist of his time had an affair with someone of the opposite sex, that would surely have become public knowledge. On the other hand, we do know that his brother Wilhelm did not allow Alexander to spend the night with a male friend at his house. But we don’t know the precise reason for that.

When your very successful book The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World came out in 2015, you said you wanted to put Humboldt back on the pedestal where he belongs because, outside the academic world, he has almost become forgotten. Was that really the case?

I’ve been living in London for almost 25 years, and I write in English. At the time, I was writing the book for the English-speaking market rather than the German. In the UK and the United States, even well-educated people have often heard nothing of Alexander von Humboldt. “Who’s that?” people in the US have asked me. You then have to spell it out: Humboldt Current, Humboldt Penguin etc. And then it finally clicks for most of them. In California, there is the Humboldt State University in Humboldt County. Even the students there think that the university is named after the county, and they’ve never asked themselves how the county got its name. Incredible! The only exceptions are the geographers who have heard of Humboldt. But to be honest, it’s not all that much better in Germany. Although Humboldt is known here, people often mix up Alexander and Wilhelm. Alexander is known as an adventurer and naturalist, but just how important he is for our understanding of the environment and of nature and also how incredibly famous Humboldt was in the contemporary world – the vast majority of Germans do not know that either. To mark the centenary of his birth in 1869, 25,000 people marched through Manhattan.