Jump to the content

- {{#headlines}}

- {{title}} {{/headlines}}

Scholars at Risk Network

More than 400 universities and research institutions in 39 countries cooperate in this network. The objectives are to protect threatened researchers and promote academic freedom. Every year, Scholars at Risk supports hundreds of researchers by providing fixed-term positions at member institutions. The network also advises host institutions and offers on-the-spot assistance for researchers and their families.

Philipp Schwartz-Initiative

The initiative grants funding to universities and research institutions in Germany which host researchers at risk on a fellowship for a period of 24 months. It was established in 2015 by the Humboldt Foundation with the support of the Federal Foreign Office and is co-financed by the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation, the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the Gerda Henkel Foundation, the Klaus Tschira Foundation, the Robert Bosch Stiftung and the Stiftung Mercator. Universities applying for funding are required, amongst other things, to submit a strategy for assisting threatened researchers.

When Nedal Said talks about the last months in his home city of Aleppo, he lowers his eyes. The Syrian microbiologist tells of a devastating civil war, of the long prison sentence meted out to his dissident brother and of the secret service that started appearing ever more often at his university and spreading terror. Back then, in 2013, he spent part of his time working at the university and part at the Department of Laboratories for Monitoring Drinking Water. “One day, a friend who had good contacts in the secret service rang me and said I was in great danger because of my opposition to Assad and should leave the country immediately,” Said reports. He quickly packed suitcases, and he and his wife and their three small children went to Turkey. When their savings ran out, the family spent a year in a Turkish refugee camp. Then, in summer 2015, Nedal Said got on a small boat – without his family – and survived the dangerous journey to his destination of choice, Germany.

“I am a whole person again”

Today, the Syrian scientist spends his time at the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research – UFZ in Leipzig and studies miniscule organisms under state-of-the-art microscopes. He speaks German – not perfectly, but amazingly well for someone who only started learning the language a year ago. “I work in science. Colleagues support me, and my family is with me at last – I am a whole person again,” says the 43-year-old, beaming.

Nedal Said is one of the first fellows of the Philipp Schwartz Initiative, a funding programme run by the Humboldt Foundation with the support of the Federal Foreign Office. It is designed to enable German universities and research institutions to employ endangered foreign researchers for a period of two years. In summer 2016, Said and 22 other selected researchers from Syria, Turkey, Libya, Pakistan and Uzbekistan had their fellowships confirmed; over 40 more fellows are due to follow at the beginning of 2017. They can all bank on an adequate salary and access to language courses and other educational opportunities.

In the contest for this coveted fellowship, dedicated mentors are important. One such is Hans-Hermann Richnow, the head of the Department Isotope Biogeochemistry at UFZ. Even before the fellowship started, he organised work experience for Nedal Said in his institute, helped with the application and made sure he had a place to work. “We were actually already looking for a microbiologist,” Richnow reports. “We found Mr Said by chance, and it had a lot to do with the fact that he himself went looking for work from the very beginning.”

“When he arrived in Berlin, Mohamed was timid and anxious – we’d never seen him like that before,” says Hilmar Schröder. But his colleague soon became his old self. Today, he holds his own seminars again and is doing a soil research project with funding from the Philipp Schwartz Initiative. Schröder and other members of the faculty are currently trying to bring Mohamed’s wife and children to Germany from a Syrian refugee camp. One colleague has provided a fridge, another saucepans and when a contract has to be signed, someone from the institute is there to help him. “I am so grateful for the support I am being given in Germany,” says the man from Aleppo who himself helps his refugee compatriots by interpreting for them – pro bono, of course.

Protected by universities

The narratives in the Philipp Schwarz Initiative tell of great danger and successful rescue. More than 60 researchers are being sponsored by the initiative and they are all part of the global stream of refugees displaced by war and persecution. Exactly how many researchers there are, where they come from, what disciplines they represent and where they find refuge is not precisely known. Some light is thrown on the matter by the statistics of the largest aid organisation for threatened researchers, the Scholars at Risk Network (SAR). More than 400 universities and research institutions around the world belong to this network; in the last two years, they have provided a safe haven for some 340 researchers. Now, 20 members of the newly founded German section with headquarters at the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation belong to the SAR Network, as well.

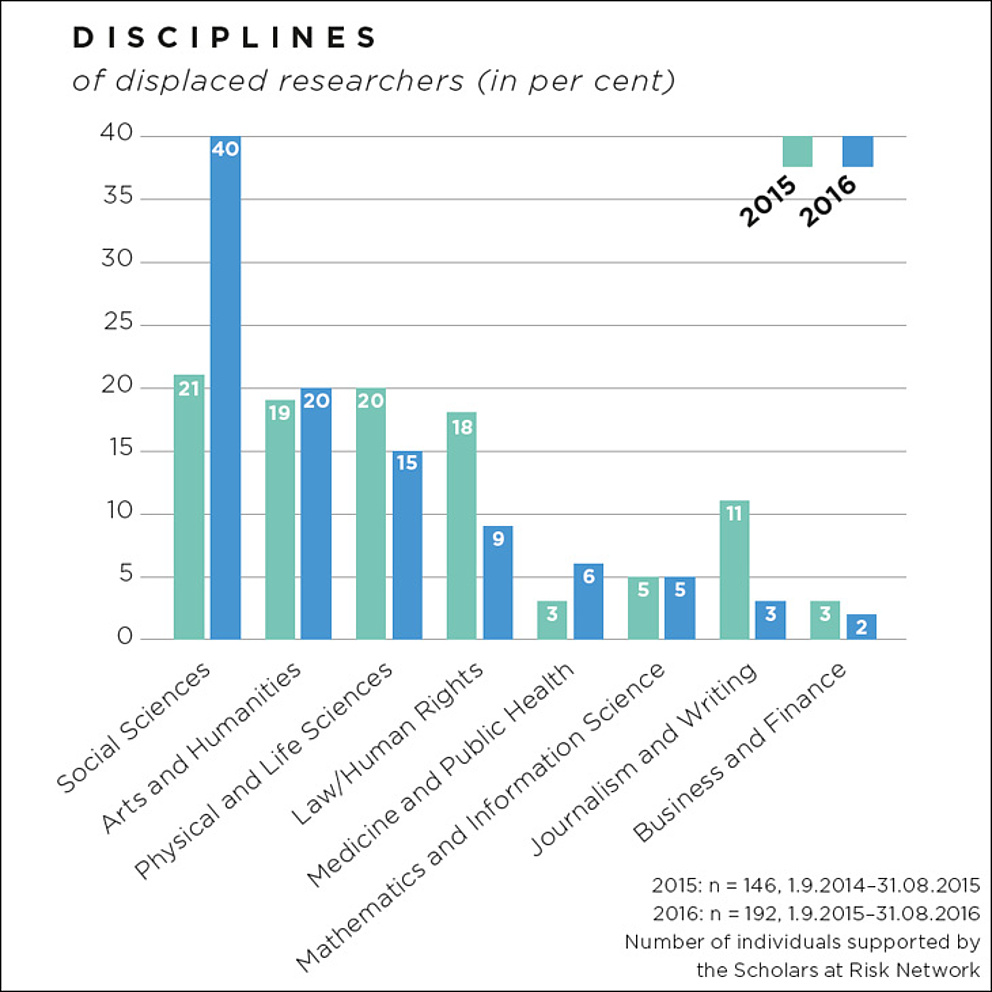

According to Scholars at Risk data, European universities accept the largest percentage of threatened researchers (see graph at the top of the page). Following major growth in Germany’s admission figures in 2016, the country now heads the European statistics together with the Netherlands. A look at the SAR statistics with reference to academic disciplines reveals that there is an increasing number of social scientists and humanities scholars amongst the persecuted (see graph above). In terms of countries of origin, Syria took over the lead from Iran in 2016 and now clearly heads the sad statistics for threatened researchers. The data also reveal that ever more Turkish academics are under threat at home (see graph below).

Meral Camcı is one of these. In January 2016, the translation scholar signed an appeal for peace against the bombardment of Kurdish territory by the Turkish government. From then on, she and some 2,000 other signatories have been subject to massive pressure. By the end of February 2016, she was given her notice as a professor; later she was arrested and released again after three weeks in custody. With the help of her mentor, the German scholar Dilek Dizdar from the University of Mainz, Meral Camcı received a Philipp Schwartz Fellowship. Since then, she has been able to stay in Germany and conduct her project on the development of feminist discourse in Turkey from a safe distance. Despite all, Camcı still travels home to do research on the spot and to support the peace movement. Dilek Dizdar is full of admiration for her intrepid colleague. “She campaigns courageously and selflessly for her convictions – this has become quite unusual in the academic world.”

The dream of peace

Most of all, Meral Camcı would like to return home to live and work. The Syrian geographer, Mohamed Ali Mohamed, also basically wants to go back, “but only if there is really peace in my country.” Nedal Said in Leipzig dreams of a peaceful future, too. Then he could work for an international company and sell scientific microscopes in the Middle East – but from a base in Europe.

Whichever way the decision turns out, “refugee researchers can be our best ambassadors,” says Said’s mentor, Hans-Hermann Richnow. He argues in favour of a special database bundling the institutes that are willing to host threatened researchers, especially as soon after their arrival as possible. “At the moment, highly-qualified specialists still lose far too much time,” the Leipzig research manager complains. He is just in the process of establishing another position for a refugee researcher in his department – this time in bioinformatics.