Jump to the content

- {{#headlines}}

- {{title}} {{/headlines}}

The threat arrived in a padded envelope: a little plastic bottle and the typed message: “drink this – then you’ll be immune.” The envelope was addressed to Christian Drosten, the virologist at the Charité hospital in Berlin who has advised the German government and public during the Corona pandemic. With his warnings he became a symbol of charting a careful course. Threats and hate messages, he reports, began arriving early on. The American immunologist, Anthony Fauci, who has been an adviser to US presidents since the 1980s, also elicited hostile reactions. In a quotation that has become legendary, he summarised his cooperation with the former US President Donald Trump, who usually ignored his warnings and advice and was openly hostile towards him, in the pithy sentence: “I was the skunk at the picnic.”

For many researchers it is a completely new experience to feel such open and aggressive rejection. Dealing with counter arguments, perhaps even scepticism, is just one of the tools of the trade. But outright rejection, even death threats? “Technology and science are increasingly interfering in areas of life itself,” says Martin Carrier, philosopher of science at Bielefeld University. “The Higgs boson doesn’t have much to fear from public opinion. But when we are talking climate, food and health, then science treads on many people’s toes.” And the more heated the societal discourse, the more responses scientists reap that comment publicly on their research topics.

There is actually nothing new about hostility towards researchers, Carrier notes and looks back in history to illustrate his point: “When Darwin published his ‘On the Origin of Species’ in 1859, people were in uproar.” The theory of evolution completely overturned religious notions of the development of life. Darwin became a target, and not just of fanatics. “Since then, when dealing with scientific outcomes, ideological issues have become ever less important,” says Carrier. Instead, research findings nowadays often inform concrete recommendations for action, from health through to climate research – and this is where they make people feel uncomfortable. So, what has mainly changed are the motives for hostility. And when some sections of the public became aware of the discussions scientists were having with each other, the questioning and checking, many went on a rant about the researchers themselves not knowing what they were doing. “Whereby there is nothing worse than consensus under conditions of uncertainty,” says Carrier who is associated with the Humboldt Foundation in his roles as an academic host, reviewer and former participant in the TransCoop Programme.

True

or

false?

How good are you at telling genuine headlines from invented ones?

October 2015 (various media)

This headline derives from a study entitled “Nail polish as a source of exposure to triphenyl phosphate”, conducted by Duke University, Durham, United Kingdom, the Environmental Working Group, Washington DC, and Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, both in the United States. The researchers explained that the softening agent triphenyl phosphate had been found in the urine of women who regularly used certain kinds of nail polish. According to the authors, it was possible that the substance could negatively impact the hormone balance of animals. The effects of triphenyl phosphate on human health, however, were not the subject of the study cited.

October 2015 (various media)

This headline derives from a study entitled “Nail polish as a source of exposure to triphenyl phosphate”, conducted by Duke University, Durham, United Kingdom, the Environmental Working Group, Washington DC, and Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, both in the United States. The researchers explained that the softening agent triphenyl phosphate had been found in the urine of women who regularly used certain kinds of nail polish. According to the authors, it was possible that the substance could negatively impact the hormone balance of animals. The effects of triphenyl phosphate on human health, however, were not the subject of the study cited.

17 November 2017 (The Telegraph)

The Italian scientist Sergio Canavero is highly controversial. In recent years, he has repeatedly approached international media to report on the purportedly sensational results of his work. But he has usually failed to provide complete documentation of his research in the field of organ transplants. The Telegraph’s headline also failed to tell its readers that the head transplant was supposedly carried out on dead bodies – and there is no actual evidence that it took place at all.

17 November 2017 (The Telegraph)

The Italian scientist Sergio Canavero is highly controversial. In recent years, he has repeatedly approached international media to report on the purportedly sensational results of his work. But he has usually failed to provide complete documentation of his research in the field of organ transplants. The Telegraph’s headline also failed to tell its readers that the head transplant was supposedly carried out on dead bodies – and there is no actual evidence that it took place at all.

14 October 2017 (The New York Post)

Are women who regularly dye their hair more prone to breast cancer than those who don’t? Answer: We don’t know. Having analysed various studies, the surgeon named as Professor Kefah Mokbel of Princess Grace Hospital in London merely concludes that more research is required. And Sanna Heikkinen, the Finnish researcher quoted in the piece, also comes to the conclusion that it may perhaps be true. But it could also be the case that women who regularly dye their hair also use other cosmetics that may increase the risk of cancer.

14 October 2017 (The New York Post)

Are women who regularly dye their hair more prone to breast cancer than those who don’t? Answer: We don’t know. Having analysed various studies, the surgeon named as Professor Kefah Mokbel of Princess Grace Hospital in London merely concludes that more research is required. And Sanna Heikkinen, the Finnish researcher quoted in the piece, also comes to the conclusion that it may perhaps be true. But it could also be the case that women who regularly dye their hair also use other cosmetics that may increase the risk of cancer.

National heroes or figures of hate

The truth, Carrier believes, is that, in the future, the issues to which science can make a contribution will continue moving ever closer to people’s “comfort zone” – such as climate change, social issues or, indeed, pandemics. How do researchers deal with this growing interest; what strategies do they choose for their communications? In the Humboldt Foundation’s network, many relevant ideas and approaches can be found – always depending on people’s research field and respective region of origin.

Rafael Radi, for example, has very recent experience of handling communications. A biochemist and Humboldt Research Award Winner, he was the leading brain behind the Honorary Scientific Advisory Group, a multi-disciplinary body that was established during the pandemic to advise the government in Uruguay. “Of course, there were negative responses, but they were marginal,” Radi reports. But he chose where he spoke very carefully: “We steered well clear of discussions that bred enmity.” Apart from this, his team produced “carefully devised public statements” that were precisely substantiated and thus difficult to refute. “When we spoke in public, we referred to these statements. We tried to keep personal opinions out of it,” says Rafael Radi. The public supported the Advisory Group, even in the most critical phases of the pandemic, actually criticising the government for implementing fewer measures than suggested. Medical practitioners in other countries can only dream of that sort of backing from the public: in some places, virologists have become national heroes during the pandemic, in others, figures of hate.

Tweeting pays dividends

Just how different communications behaviour can be, is something Katharina Pistor (on Twitter @KatharinaPistor) observes time and again. The German legal scholar is a professor at the distinguished Columbia Law School in New York and an enthusiastic Twitter user. “The tone on Twitter is more relaxed in the US,” she observes. “Responses are less brusque and condescending than in Germany, for instance.” Pistor’s posts cover current legal decisions in her special fields of corporate, business and transactional law as well as topics like graduation celebrations at her university or even the neighbour’s dog, Cucchi. “At the beginning, I was sceptical and thought tweeting was just eating up my time,” says the Max Planck Research Award Winner. But she decided to have a go. That was three years ago when she was writing her legal book for non-specialists, “The Code of Capital”. “I wanted to promote it on social media and resolved to have 1,000 followers by the time it was published,” she says. She easily achieved her goal – and became an enthusiastic user. “You discover a lot about what’s going on, not least from people that you wouldn’t have much to do with otherwise,” Pistor concludes. Thanks to Twitter, she finds out about colleagues in other parts of the world, researchers from other disciplines and good books. And she shares her own thoughts: “If you enjoy the luxury of being able to think about things in peace, you should also share your thoughts with a broader public,” she says. Nasty comments are the exception, which certainly has to do with the topics After all, legal issues are seldom genuinely polarising – but some posts do make emotions run high, even on her channel: “When I comment on bitcoins, for instance, I notice that this topic attracts a more aggressive target group,” Pistor reports.

The tone on Twitter is more relaxed in the US.

For other researchers, however, communicating their research too openly on social media is risky. One example is Karen Radner Humboldt Professor at LMU Munich. She is one of the most eminent experts on the Ancient History of the Near and Middle East – a region where the political situation is tense and often confusing. “On principle, I never comment on political issues, neither in interviews nor on social media,” says Karen Radner. A critical remark, even an interpretable comment could have a cascade of consequences. For her digs and fieldwork she is reliant on acquiring permits from the governments responsible, and they usually screen applicants. Moreover, there is a danger of being targeted by fanatics, which could be a problem not only for her herself but for the team on the spot. “I always tell my students and staff: ‘If you insist on posting, you should take care that your comments won’t have any negative implications for yourselves and your team’,” Karen Radner explains. But she also knows that the public sphere is an inherent part of research – she writes books for non-specialists, publishes on specialist websites and heads an online course for members of the general public. “I concentrate on exclusively talking about my work,” she says.

On principle, I never comment on political issues, neither in interviews nor on social media.

When climate researchers talk about their work, they find themselves knocking on open doors. Theirs is a hot topic, their findings influence policies all over the world. But not everyone is enthusiastic: climate experts report repeatedly on hostility and threats. This leaves Eduardo Queiroz Alves unfazed. The geochemist, a Humboldt Research Fellow at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven, investigates the impact of melting permafrost on the Earth’s climate. “Lots of people think research on the climate crisis is a kind of black box. They hear scientific forecasts and recommendations but simply cannot imagine how they are arrived at,” says the Brazilian. In his words, he therefore wants to “demystify” the work of climate scientists and invite those who are interested into his lab – virtually. And he puts a great deal of effort into doing so: he holds lectures for students and school children, he tweets and blogs. He has just taken part in the Communication Lab for Exchange between Research and Media that is run jointly by the Humboldt Foundation and the organisation International Journalists’ Programmes (IJP). Researchers like Queiroz Alves share ideas and experience with journalists on communicating science and prepare journalistic products together.

“Up to now, I had largely written for colleagues and find it quite difficult to discover the voice I should use to speak to the general public,” he says. Then he grins. “During the programme, one journalist asked me to write a short summary of my work. She read the few lines I’d written and said, ‘I don’t get it at all.’ So, I wrote it sociagain and again until I’d figured it out.” For his posts, he adopted a different style and made YouTube videos together with a science journalist. And, in no time, he received a message from his sister in Brazil: “Wow, I’ve understood it at last,” she told him. “I never really knew exactly what you were working on!” That is the sort of response many researchers would like to receive to their communications. They want to show what goes on behind lab doors and make clear how science really works – and why it doesn’t always have an answer to everything.

Acquiring knowledge-process in real time

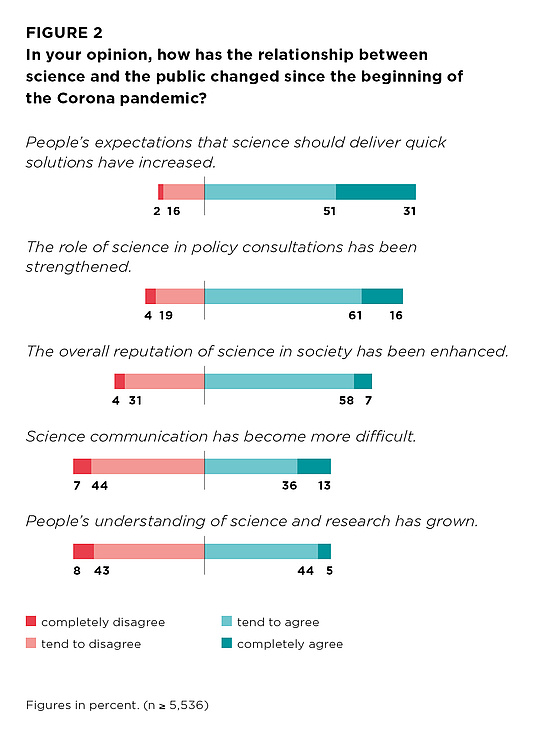

The Covid-19 pandemic has taught us a lot, according to the President of the Humboldt Foundation, Hans-Christian Pape: “The public have witnessed the process of acquiring scientific knowledge in real time with all its provisionalities and hypotheses, which have to be checked, confirmed or, indeed, disproved multiple times.” The fact that scientific recommendations on issues like the suitability of vaccines for specific age groups changed, led to a degree of discontent amongst the population and politicians. Pape argues for dealing with changes in the evidence base in a sober, open way: “The division of labour in our society tasks science with providing the best possible knowledge available. It should not behave as though it had oven-ready solutions to every problem but must openly admit to uncertainties. It must refrain from promising society any kind of panacea – that leads, on the one hand, to science making excessive demands on itself and, on the other, to an excess of hope and expectations.”

Longing for solutions

But even when scientists are modest and realistic, they often encounter huge expectations which have grown historically. “In the last few decades, science and technology have been very successful. That has spoilt society,” says Martin Carrier, the philosopher of science from Bielefeld University. “Thanks to research, quick solutions have been found to many problems. So, it’s difficult to keep your expectations realistic about what science can achieve.” And that was precisely the case when the entire world suddenly felt at a loss as to what to do about a novel virus, and even science couldn’t immediately come up with a magic solution. Martin Carrier’s thoughts return to the past, and he grins. “Do you know the anecdote about Woodrow Wilson?” he asks. During the First World War, the US president appointed a physicist to his consultative board, justifying the choice with the legendary words “in case we have to calculate something out.” This historical sentence embodies the contempt that was felt for science, says Carrier. How very different the situation is today, despite occasional bouts of science scepticism. “I think it’s a positive signal that science gets reactions from society.”

In the last resort, it proves that it is perceived as relevant.

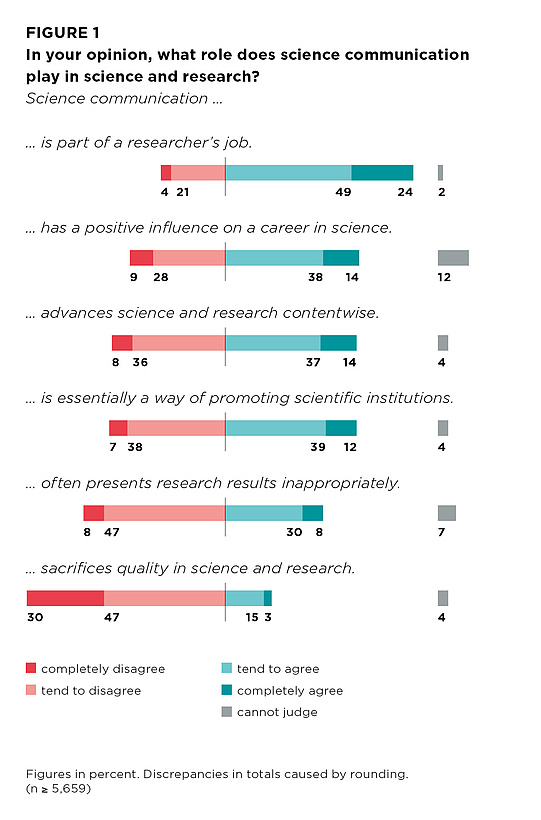

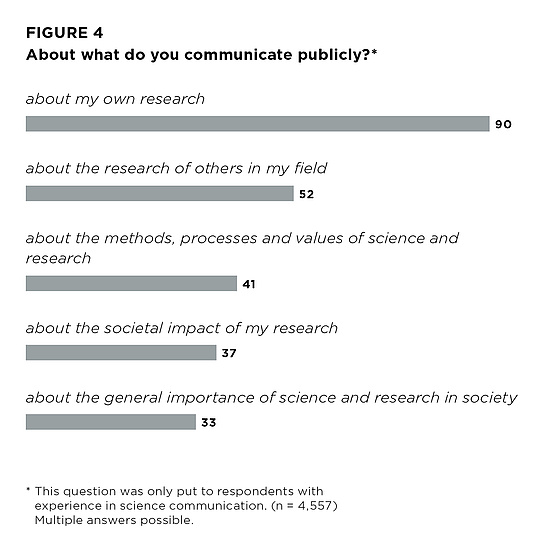

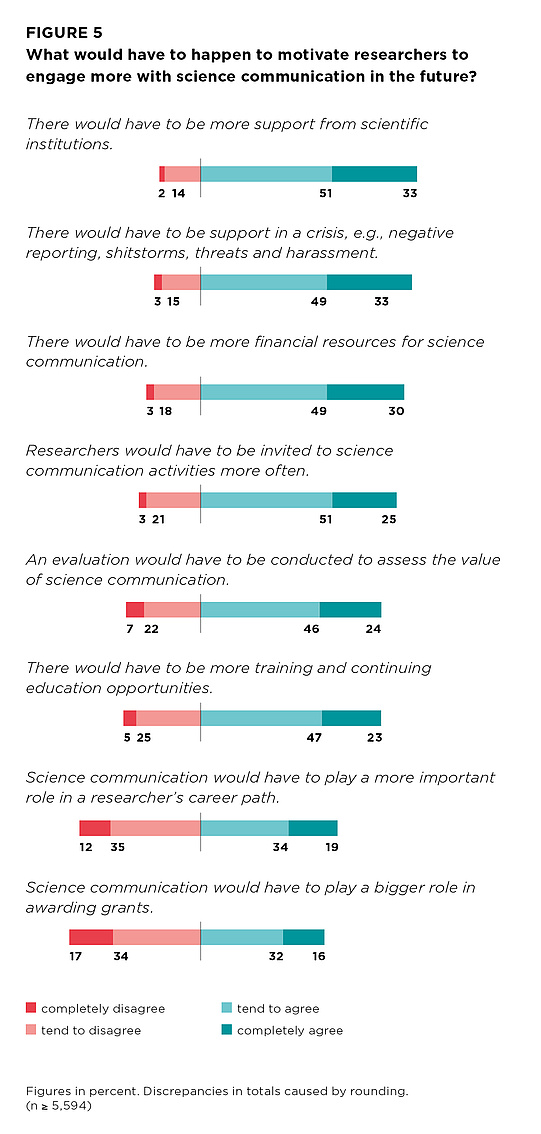

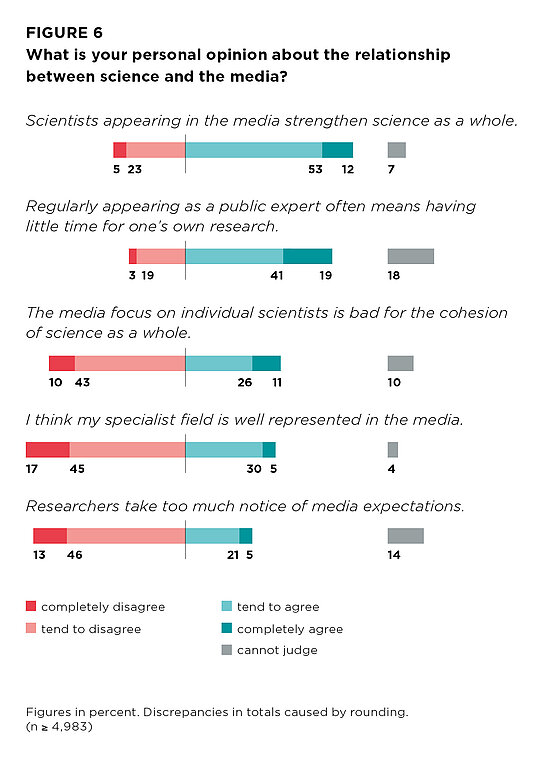

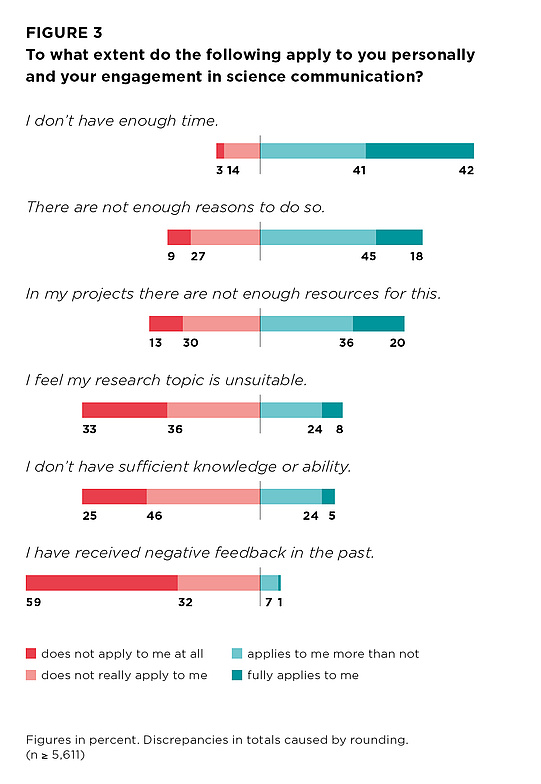

Source for all figures: Science communication in Germany: results of a survey of 5,688 researchers at German universities and non-university research institutions conducted by the Impact Unit of Wissenschaft im Dialog, the German Centre for Higher Education Research and Science Studies, and the National Institute for Science Communication.