Jump to the content

- {{#headlines}}

- {{title}} {{/headlines}}

It smells like meat, looks like meat and, if the test subjects are to be believed, tastes like meat, too. But there is nothing animal about this meatball, it is entirely vegetable. Scientists at Impossible Foods spent five years tinkering with the recipe before they launched their vegan burger in San Francisco in summer 2016. It is soon due to hit the restaurants big time – with the support of Bill Gates, Google and other top-notch investors.

Silicon Valley may have just taken the lead with its plant-based burger but the idea of cultured meat originated in Europe. Back in 2013, the Dutch medical scientist Mark Post produced a rissole, cultivated in a complicated process from the stem cells of cattle, at a cost of 250,000 euros. But with the startup Mosa Meat, he is about to launch a stem cell meatball at an affordable price. According to Post, the production costs have now been reduced to roughly 10 euros a burger. The competition, however, is hot on his heels. With money pumped in by big financial investors, new firms are popping up all over the world and researchers are developing cultured meat patterned on pork and chicken as well.

Meat is more than just a foodstuff, it has become the symbol of a global crisis. Approximately a third of the world’s entire land area is currently devoted to meat production. The animals pollute the soil and water with their excretion and accelerate climate change with their emission of greenhouse gases. And although it is known that a big appetite for meat can make you fat and ill, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the annual per capita consumption of meat in industrialised countries is an impressive 96 kilos; in poorer countries consumption is growing fast. At the same time, the population is growing, too: United Nations’ figures show there are 7.6 billion people living on Earth; by 2050, it will be ten billion and by 2100, more than eleven billion. Everyone wants to satisfy their hunger and feel comfortable. But how can it be done?

Thirty-Storey High-Rise Farms

This is a question preoccupying people all over the world. It does not just attract the attention of scientists and clever investors seeking to fill our plates with cultured meat, cultured fish and the like. Hightech prophets are also joining the fray with visions of 30-storey high-rise farms supplying entire mega cities with vegetables and fruit – or scenarios involving 3D printers for our own kitchens with jets dispensing not ink but pureed food – adapted to our personal gene profile and containing everything the body needs. This would not be a million miles from the daily food capsule utopians were predicting a good hundred years ago but which, thankfully, never came about. Instead, the shelves of food in the rich part of the world groan under an amazing abundance of goods and ever more people pay homage to particular dietary regimes.

“Never have people talked so much about food as they do today,” says Hannelore Daniel, nutrition researcher at the Technical University of Munich. In our western lands-of-plenty many people have lost their way: they long for the supposedly ideal food world of yesteryear or turn the act of eating into a kind of ersatz religion, she notes. From veganism to the paleo diet, the wholefood boom and superfoods, the field is teeming with those searching for meaning. Daniel’s diagnosis: “We have reached the metaphysical stage of nutrition.”

The sound of waves sparks a fancy for fish

Sensual enjoyment does not have to get forgotten in all of this. How it can be cleverly increased by psychological insights and modern communications technology is described by the British psychology professor Charles Spence in his new book “Gastrophysics: The New Science of Eating”. It has been proven, for example, that fish tastes better if it is accompanied by the gentle sound of waves. “It wouldn’t surprise me if the waiters of tomorrow bring us headphones as well,” says Spence, a Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel Research Award Winner who heads the Crossmodal Research Laboratory at the University of Oxford.

Even today, in some restaurants, grilled food is served on a tablet with flames burning on the screen and the sound of a sizzling wood fire blended in. The experience enraptured many guests, reports Spence, who thinks tablets are likely to become tomorrow’s plates. Musical spoons, on the other hand, that do not just transport Indian curry into our mouths but – inaudible for other diners – the sound of sitar music as well, are not likely to catch on. He is also critical of the first 3D food printers for the home: “They’ll end up at the back of the cupboard collecting dust.”

Insect cuisine, by contrast, could be looking ahead to a golden age: “Even in our part of the world, we’ll soon be eating ants, termites, locusts, appetisingly prepared by small specialised firms” – possibly accompanied by the consciousness of consuming ethically irreproachable proteins. “People are spending more and more time thinking about their food,” Charles Spence has observed. He predicts a great future for the sustainability trend.

That is precisely the aim of the philosopher Harald Lemke. The Humboldtian sees himself as a representative of gastrosophy, a school of thought that studies both the wisdom of eating as well as the political dimension of nutrition. “When you eat,” says the director of the International Gastrosophy Forum in Saalfelden, Austria, “you don’t just fill your stomach, you establish all kinds of connections with the world” – with animal ethics and health as well as with land ownership and climate change. Lemke does not, however, argue for the ethics of renunciation but, rather, for seeing cooking and savouring as a consciously responsible art of living. The gastrosopher is under no illusions: although the number of mindful eaters is growing there will still be plenty of people in future who opt for convenience foods and cheap, factory-farmed meat. “A sustainably managed and just world in which everyone benefits equally from existing resources is probably just a lovely dream.”

Under pressure from a burgeoning population, global resources will have to be increased significantly. Apart from glamourous visions for the future, there are also some sensible ideas that hold considerable promise of success. What they can achieve is demonstrated by the work of the agricultural scientist and Humboldtian Michael Frei from the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at the University of Bonn. He conducts research on rice, a staple foodstuff for more than half of humanity. Stress factors such as heat, salt water and high ozone levels in the air have an impact on today’s highly-hybridised varieties, and yields are already dropping noticeably. “We urgently need new varieties which can cope better with increasing environmental pressures,” says Michael Frei, who has already hosted a number of Georg Forster Research Fellows in his team. The Bonn scientist’s record to date is nothing to be ashamed of: in collaboration with growers from Bangladesh, rice hybrids have been produced that could come on the market in a few years’ time. “They not only cope with ozone,” says Frei, “they could even yield up to ten per cent more than previous top varieties.”

Having enough to eat is one thing, eating properly is another. But why are some foodstuffs better for some people than for others? This is the question food chemist Thomas Henle of TU Dresden is investigating. “So far, we know far too little about the fate of food in our bodies, especially from a chemical point of view,” says the scientist, a Humboldt host who often mentors Foundation fellows at his institute. In his research, Henle concentrates on the activities of intestinal bacteria and their metabolic products in degrading cooked food. He hopes to be able to identify defects in the digestive process and starting points for therapies. “Perhaps we’ll even be able to develop personalised intestinal diets for nutrition-related diseases,” says the Dresden scientist.

Hannelore Daniel, the Munich biochemist, is putting her money on a different individualisation strategy: “The future is personalised nutrition that takes account of the interplay between food, metabolism and genes.” International food giants are already pushing hard in this direction, according to Daniel. Nestlé, for example, has declared personalised nutrition to be one of its corporate goals. In autumn 2016, the American soup producer Campbell earmarked 32 million dollars to invest in the Silicon Valley startup Habit. The Californians design individual meal plans based on a genetic self-check and are looking to deliver ever more tailored meals in future.

High time for a turnaround

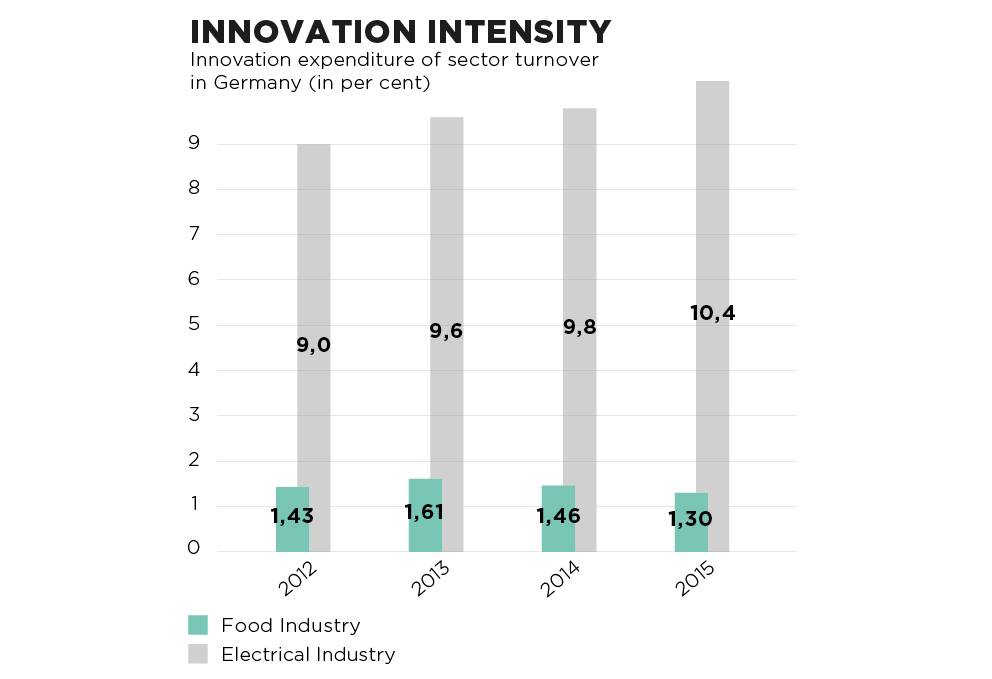

Whilst food innovation in the United States is booming, the same cannot be said of the food industry in Germany, which is characterised by small and medium-sized businesses. Innovation expenditure is even dropping slightly (see diagram on page 23) and was recently 1.3 per cent of the entire sector’s turnover. By comparison: in the electrical industry, the share was 10.4 per cent.

Hannelore Daniel thinks it is high time for a turnaround, which should be ushered in by a significant upgrading of nutritional science. “We need large-scale studies, for example, that can prove the health impact of certain diets in comparison with control groups.”

Still, at least at European level, there has been some movement in nutrition research. After completing the EU project Food4Me, which created the basis for research into personalised nutrition, a 1.6 billion euro innovation programme called EIT Food is being launched for the food sector involving 50 universities, companies and research centres across Europe. “We want to develop new food products for personalised, healthy eating that also take account of the needs of an ageing population,” says Jochen Weiss from the University of Hohenheim, one of the founding directors of EIT Food.

Now that investors in the United States have discovered the agri-food sector, roughly ten times as much risk capital is flowing into this area today, as compared to five years ago. “We have to reckon with a wave of American startups that will put enormous pressure on established companies in Germany and Europe,” says Jochen Weiss. EIT wants something up its sleeve to set against this, such as establishing 350 startups of its own.

Cultured meat and insect snacks, high-rise farms and pizza printers are probably just the beginning. In the coming years, we will be surprised by a lot of new ideas. The world certainly needs them.

Source diagram "Innovation intensity": Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW), Sector Reports on Innovation 2016 – Food, Drink and Tobacco Industry, and Electrical Industry