Jump to the content

- {{#headlines}}

- {{title}} {{/headlines}}

Rüdiger Schaper is head of the cultural affairs section at the Berlin daily Der Tagesspiegel. His biography, „Alexander von Humboldt – Der Preuße und die neuen Welten“ (Alexander von Humboldt – The Prussian and the New Worlds), was published by Siedler Verlag in 2018.

If Humboldt were on twitter today

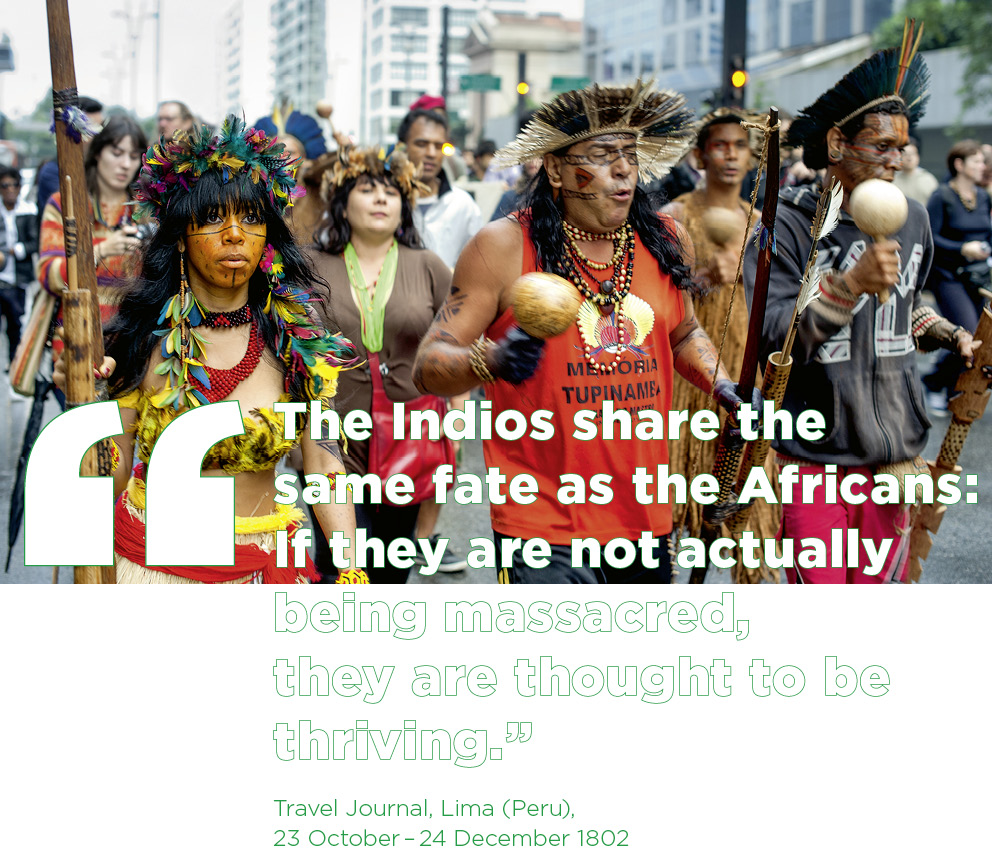

For more Humboldt quotations on images from today, visit here.

The great minds of his time, whether Kant, Goethe or later Karl Marx, largely explore the world from the comfort of their own writing desks. But Alexander von Humboldt not only tries to explain the world, but ventures where no one has gone before. He experiments on his own body and puts his life at risk, as though there were more to be had where that came from. As a young mines inspector in Franconia, he almost suffocates in a mineshaft, aged 24. He is already delirious when he is found and brought to the surface. Just a few years later, during a trip down the Orinoco River, the boat carrying the Prussian Columbus threatens to capsize. Humboldt can’t swim, and the water is infested with crocodiles. He has another narrow escape, just as he does when a wall of snow breaks loose right beside him and plummets into the depths as he is climbing up a volcano in the Andes. On the crossing from Havana to Cartagena in today’s Colombia, his vessel just manages to avoid a shipping accident. In the jungle he has an encounter with a jaguar but gets off lightly. Humboldt knows exactly how to cleverly incorporate these episodes both into conversations and his writings.

Like an extreme athlete

The long life of this researcher and writer is full of close calls and endeavours that defy reason. Aged 57, Alexander von Humboldt climbs, extreme-athlete-style, into a diving bell and has himself winched to the bottom of the Thames. This is the time when London is building the first tunnel under the river. It is pitch dark and freezing cold down amongst the sewage. The bell descends eleven metres, and its occupants are fed oxygen through a leather hose. Humboldt’s head pounds, the pressure changes make him bleed from the nose and he remembers his madcap tours in Latin America.

Humboldt combined natural science and the humanities in an exemplary fashion and that is something that exerts great appeal again today, inspiring both artists and scientists. As he writes in the first volume of “Cosmos”, Humboldt wanted to comprehend “the phenomena of physical objects” in their general connection. In the end, “everything is interconnected.” And so much of what occurs in his working life – apparently so meticulously organised – is really just coincidence. Before setting off for America, he has other plans. He wants to go to Egypt, then on to Asia, but this all falls apart, luckily, as it turns out, because in 1799, the Spanish crown unexpectedly issues him and his colleague Aimé Bonpland passports to visit the New World. The Spanish hope this supremely self-confident, but also diplomatically-versed, mining expert will contribute new expertise to their badly-organised silver mines in the colonies. Humboldt had speculated on this happening, but he couldn’t bank on it.

The self-promotion genius

This free, radical element is typical of Humboldt’s entire existence. When it comes to grasping opportunities and setting forth, he has an uncanny feeling for the right moment. And after but a few months of travelling around Latin America, he gives us a taste of his genius for self-promotion: In a letter to an American businessman of German descent he describes his travel experiences and asks him to post a notice “in one or two of the most widely-read American newspapers (the ones that go to England).” Unashamedly brazen, he delivers the copy himself, in detail and in the third person, ready for publication: “that after having conducted the physical and mineralogical observations on the summit of Pico de Tenerife, Humboldt arrived with his collection of physical and astronomical instruments in very good health and happy at Cumaná Harbour at the beginning of July, from where he has already commenced his work in the mountains of Paria and Nueva Andalucia under the protection of his Catholic Majesty. From here he will proceed to Mexico.”

So spoke the networker and the daredevil. They are professionally chosen words, designed to spark curiosity, proclaim his deeds and keep his audience, especially in Europe, informed and amazed. The plan works – the journals play along. Humboldt’s self-promotion is thorough and systematic. He knows who could be of use to him, where and under what circumstances – irrespective of whether they are a king or a merchant, an academic colleague or a university friend with connections. The world should be told how he manages to broaden its horizons. He has this self-publicity thing down to a T: how you present the image the world makes of you – it is the creation of a global brand.

In the letter cited here we notice how hurriedly it was composed. Humboldt writes letters – lots of letters, 50,000 reportedly over the course of his life – the way e-mails and tweets are produced today. His five-year journey around South, Central and North America, at the end of which he meets US President Thomas Jefferson and revels in the compliments heaped upon him, is followed by fifty years of uninterrupted publishing activity. Alexander von Humboldt goes about writing and publishing his books with the same dynamism, daredevil mentality and obsession he has previously devoted to mountains, rivers, oceans and scorching hot regions, not to forget their people and cultures.

Something cold, something armourplated about him

“With contemplation and energy, you can survive anything,” notes the traveller whose health never suffers, even under extreme conditions, but seems to thrive under the constant exertion that knocks other Europeans off their feet. There is something cold about him, something armour-plated, and he easily irritates his contemporaries and hurts their feelings. Humboldt combines emotion and analysis without mixing them up. He cultivates calculating admiration and admiring calculation.

The American travel narratives are a huge undertaking, a publishing nightmare, economic madness, a labour of Sisyphus. Depending on how you count them, there are a total of 35 volumes: a library of the New World with maps and numerous illustrations. This is all coordinated by one single person who employs a small army of specialists – printers, illustrators, translators, publishers, scientific staff and co-authors. The volumes are usually published in French, sometimes in German translation, whereby the German version is not always the work of Humboldt himself. Some of the books appear in English even before 1815. There are translations into Dutch, the language of another colonial power and, later, into Spanish. His book on Cuba is banned on the Caribbean island because of its political content. Humboldt – an engaged abolitionist – writes about geography and sociology, flora and fauna, climate and art. It is the largest encyclopaedia ever produced privately. It impoverishes the author and drags others into financial ruin along with him. Some of the volumes are so expensive that Humboldt himself can’t afford them. When he returns to Berlin in 1827, he is not only famous but effectively bankrupt.

Data conjoined with poetry

The “Cosmos” volumes that are published by Cotta from 1845 onwards are not part of the actual travel narratives even though they do correspond with them. They are a universe of their own and become best-sellers. By 1858, four volumes have appeared. They are devoted to the structure of the Earth and celestial phenomena, the history of culture and science, as well as – and this is one of the things that makes Humboldt stand apart from others – “enjoyment of nature” and aesthetic empiricism. From the “cycle of objects” he moves on into the realm of emotions and so, for him, it becomes a case of sensual science, data conjoined with poetry, especially in the second volume. Humboldt is unable to finish the fifth volume of “Cosmos”: he dies in 1859, just short of his 90th birthday. The project could never have been finished anyway – that is in the nature of the beast – something he is constantly aware of whilst carrying out this overwhelming task.

Research has a goal, but never an end. Humboldt himself ensured that this was the case by ceaselessly encouraging and supporting young researchers. “Cosmos” appears at a time that experiences an explosion of knowledge and a radical change in scientific practice. Even if his name is the only name on the cover, he did not write the whole of “Cosmos” himself. Humboldt is a collector of people and contacts. The State Library in Berlin holds his address book in which he more or less alphabetically noted his contacts with their names, professions, private or hotel addresses and other information: a total of 900 names and addresses – cramped script and barely legible, like most of his manuscripts. He uses every square centimetre of paper. Cross-references, circular motions – this is what work on the “Cosmos” volumes looked like. Humboldt sends manuscripts to friends and colleagues asking for their feedback. He involves hundreds of scientists in collating information from the most diverse areas: the Wikipedia of the 19th century. He builds up his network so that many young researchers in his orbit are able to benefit from. He doesn’t only circulate data and commentaries around the world, but also information on jobs and positions. Humboldt’s networkers often communicate with one another about things without referring to “Cosmos”. There are specialist advisors for each main area. Humboldt and his cosmonauts don’t want to miss out on the newest developments. From them, he collects, updates and optimises state-of-the-art knowledge. An endless undertaking: some of it is soon outdated or already obsolete.

Many Humboldts, many projection surfaces

Alexander von Humboldt didn’t bequeath any earth-shaking theories like Charles Darwin, who revered him. Rather, he provides intellectual tools, open-minded ways of thinking, holistic points of view, all of which have turned out to be amazingly useful in the early 21st century’s surge in globalisation: let’s call it the Humboldt Code. Major celebrations are planned for the 250th anniversary of his birth in September 2019; his name is in everyone’s mouth, and politicians have frequently taken to quoting him. The tone generally adopted verges on veneration, despite the fact that there is not just one Humboldt, but many Humboldts and many projection surfaces. We see the German researcher and thinker who finds inner peace in the jungles of Spanish colonies, the Berlin-born author who writes many of his books in French. We follow the European who spends a third of his life in Paris and, well into old age, says that he considers himself – in his own words – to be half an American. And sometimes we look in awe at the man who reveals so little of his private life and whose legacy is far from having been studied exhaustively. We still have some discoveries to expect, or even surprises.

published in Humboldt Kosmos 109/2018