Jump to the content

- {{#headlines}}

- {{title}} {{/headlines}}

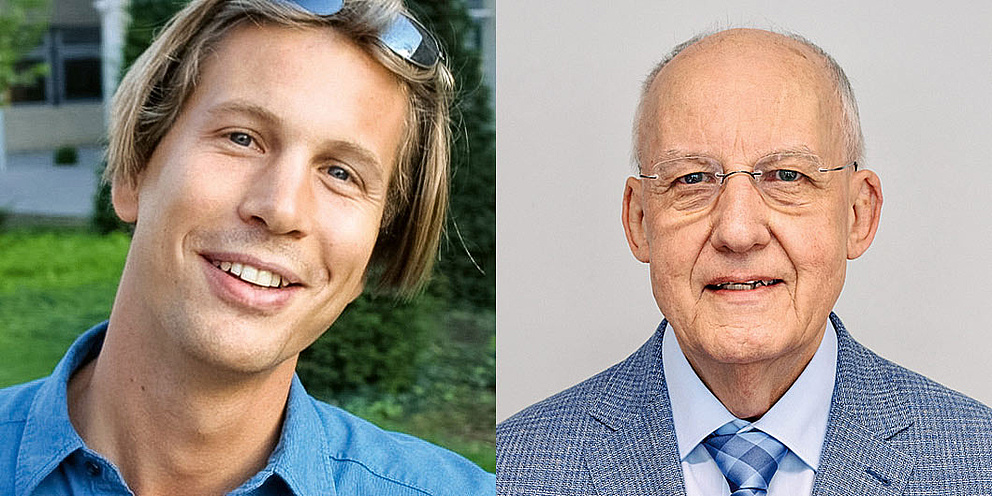

Professor Dr Bence Nanay was granted the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation’s Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel Research Award in 2016 for his achievements in the philosophy of perception, aesthetics and philosophy of mind. A professor of philosophy at the University of Antwerp, Belgium, he is also co-director of the Centre for Philosophical Psychology. Working at the intersection of philosophy, psychology and cognitive science, Nanay’s special interest focusses on aesthetics as a philosophy of perception.

Professor (em.) Dr Alexander Thomas is a Humboldt host and emeritus professor of social and organisational psychology at the University of Regensburg. He is the author of standard textbooks on the cultural standard concept, which he established, and on intercultural competence.

It is always a risky undertaking to spend time studying in another country. We set off with a suitcase full of expectations, prejudices and at least two decades of experience in a different cultural environment which often unconsciously shape our behaviour, values and preferences. “An intercultural encounter can thus be extremely enriching, reaching beyond our previous horizons,” says Alexander Thomas, emeritus professor of social psychology at the University of Regensburg. “But it can also lead to confusion and failure.” How we experience a host country and get along there depends on a raft of factors.

Our perception of people and events alone is already much more individualised than we assume. Even fundamentals like colours and forms can be differently perceived, although we all use our retina’s rods and cones to see them; the biology of sensory perception has a universal basis. “But what we see is the result of a brain process which is shaped before we are born and constantly updated by our experiences,” explains Bence Nanay, philosopher at the University of Antwerp.

One person sees fish, the other air bubbles

Just how big the differences in perception can be are demonstrated by comparative cultural experiments. Researchers have discovered, for example, that the Himba – an indigenous population of northern Namibia – perceive the Ebbinghaus Illusion quite differently from the average European. This optical illusion shows two identical circles. One is surrounded by smaller circles, the other by larger circles. The latter appears to be considerably smaller than its twin. But the Himba are not hoodwinked by what is going on round about. They recognise fairly accurately that both central circles have the same radius. And there is an underlying cause for this: in the language of the Himba there is no word for circle. Round objects hardly play any role in their everyday life at all.

“The more often we see, hear or experience something, the more likely it is that we will develop a preference for it.”

As many studies have now shown, the visual perception of Asians and people from western cultures diverges significantly, too. “Whereas a Westerner just sees a fish in an aquarium and thus merely the central object, Asians also see additional details in the vicinity, such as bubbles rising to the surface and the plants in the water,” as Nanay illustrates. The reason for this holistic perception, according to experts like the American psychologist Richard Nisbett, is their collectivist social system in which “we” is much more important than “I”. Here in Germany, on the other hand, individualism is dominant.

We like what we are used to

“In the course of our lives, people who are close to us influence us. First our parents, then the circle of close contacts gets bigger and what we consider to be normal establishes itself,” Nanay explains. The more often we see, hear or experience something, the more likely it is that we will develop a preference for it. This even happens in a seminar situation: the more often people have met on a course – even if they have never spoken to one another – the more they like each other. Most of all, we like the things we are used to. This connection is so well documented that it is described in countless psychology textbooks as the mere-exposure effect.

“Good as Germany is as a research location, it gets much lower marks on the personal level.”

“The mere-exposure effect leads to a situation in which visiting researchers from abroad may be quite curious and open about our health system, but still miss the familiar structures in their own countries,” analyses Nanay. Before they can begin to really like the particularities of their host country, they go through a phase of acculturation stress. They are forced to keep asking questions and learn to find their way around by having good and bad experiences. Because of the way our specific culture has shaped us, combined with the mere-exposure effect, we always see our host country through the eyes of our own experience. We compare childcare options, professorial supervision and our contacts with other academics with an internalised cultural standard, believes Alexander Thomas. “For someone from China, for instance, the way you are supervised by a professor here would take some getting used to,” he says. “In China, work and personal life are interwoven. A Chinese professor also has a pastoral role and is the go-to person in emotional crisis situations.”

Country of deadlines and milestones

Typical German cultural standards can also be distilled from the feedback provided by the various different nationalities, according to Thomas. The world of work here in Germany seems highly structured. Time-planning involving deadlines and milestones plays a major role. Collaboration is governed by many, in some cases unspoken, rules. Politeness norms require communication to be direct and truthful. A member of staff may, for instance, openly adopt a critical attitude to a professor’s suggestion. In the Arabic speaking world, this would often amount to a defamatory revolt against authority. Only when you spend more time somewhere do you come into contact with different cultural standards. Varying thought and behaviour patterns are then revealed that cause confusion when encountered. “Visiting researchers need to be prepared for unexpected reactions and unforeseen behaviour,” says Thomas, “and they need to come equipped with a good portion of tolerance and empathy in order to gradually settle into the other culture.”

Unconscious codes of values

In the course of our lives in our own cultural area, we acquire an unconscious code of values. It comprises highly complex, unwritten rules of behaviour and language: a kind of traditional, constantly evolving book of everyday etiquette. We know who to hug when we meet them, how to introduce ourselves and what a doctoral degree ceremony involves. But all foreigners – be they British, French or Spanish – are initially at sea when it comes to the complicated, unwritten code of values in Germany. A French welcome kiss would certainly confuse a German host. To lean over the table to chat to the people at the next table, as happens in Italy, would raise some eyebrows, and to get up and dance at the least suggestion of Spanish music in any bar, with or without a dancefloor, would definitely constitute a minor sensation.

Many fellows regret to note that it is hard to make contact with Germans. Good as Germany is as a research location, it gets much lower marks on the personal level. Which is no surprise, there are the language barrier, the unfamiliar code of values and the German tendency to keep foreigners at arm’s length. A stereotype that Alexander Thomas has often encountered offers some consolation: “Once you have finally managed to make friends with a German, you have a friend for life. This piece of wisdom about us does the rounds in other countries, too.”

published in Humboldt Kosmos 110/2019