Jump to the content

- {{#headlines}}

- {{title}} {{/headlines}}

Kofi Yakpo

Professor Dr Kofi Yakpo is an associate professor of linguistics at the University of Hong Kong, China. In 2020/21, he was a Humboldt Research Fellow in the Institute of Asian and African Studies at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Under the stage name “Linguist”, he and his band, Advanced Chemistry, wrote musical history. Yakpo has also written plays and short stories and was the recipient of the 2004 May Ayim Award for Black German Literature.

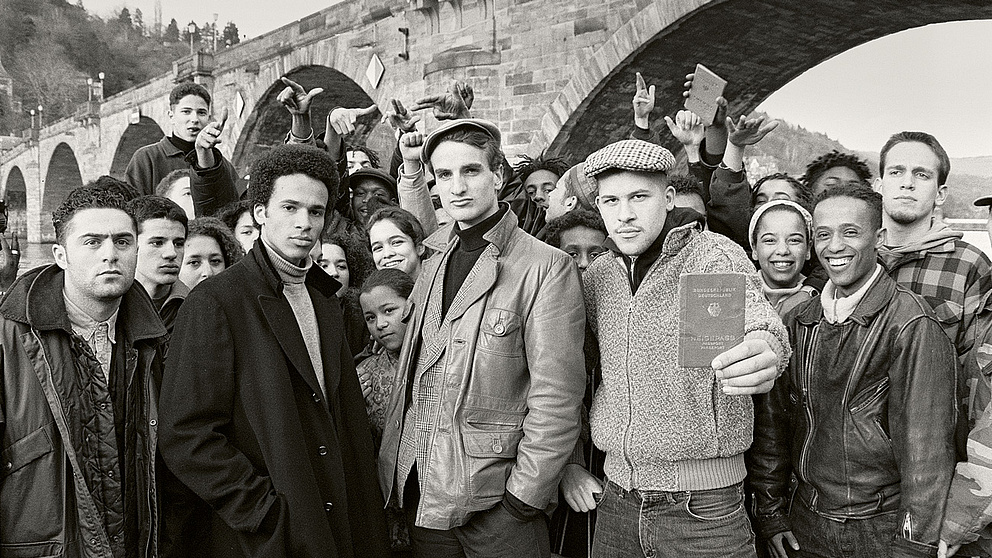

Twice in his life, Kofi Yakpo has made a name for himself as a linguist: Once as a rapper in the German hip-hop band, Advanced Chemistry, where his stage name was “Linguist”. The 1992 single "Fremd im eigenen Land" (Foreigner in my own country) made the band famous whilst his academic career only began shortly before his 40th birthday.

Since 2013, Yakpo has been teaching linguistics at the University of Hong Kong und conducting research into Afro-Caribbean Creole languages: languages that develop when two or more languages converge and form a new one. This kind of hybridisation emerged during the colonial era, the linguistics professor explains, often under duress. And although there are nearly 200 million speakers of Creole languages worldwide, unlike European languages, so far, they have often not been studied sufficiently.

At the time I thought, if I can entertain a thousand people, I can become a professor, too.

The fact that he has this second career as a researcher at all, says Yakpo, is not just a result of his huge interest in languages but also because of his hip-hop outlook. “As hip-hoppers, our attitude was: I am large. We were always brimming with confidence.” At the time of our video conference, Yakpo is in Nairobi, Kenya, where he is exploring the linguistic variants of Swahili.

The turning point, that is, the moment he decided to focus exclusively on research, came in 2008. He was working for Thilo Hoppe, then a member of the Green Party in the Bundestag, as a political advisor on food security in Africa. “I was living a sort of double life,” he says and laughs. One part was his work at the Bundestag, the other his research in linguistics. Alongside that, he completed his doctorate: the first complete grammar of Pichi, an Afro-Caribbean Creole language. When it was finished, he showed it to colleagues at the Bundestag, Yakpo relates. “One person leafed through and said: I don’t understand it at all. That’s totally different from what you do here. Either you’re an impostor or you have a split personality.” That was when Yakpo realised that he had to plump for linguistics, his true passion.

We didn’t respect limits

“At the time I thought, if I can get up on stage and entertain a thousand people, I can become a professor, too,” says Yakpo and has to laugh again. That was his hip-hop ego speaking. “It was just the way we were on the hip-hop scene. We knew there were limits, but we didn’t respect them.”

After a three-year stint as a postdoc in the Netherlands, he started looking for jobs worldwide. “Academia in Germany was too complicated and opaque for my liking,” he explains. “I couldn’t understand how you could make progress as a researcher in Germany, so I didn’t bother to apply there in the first place.” In Hong Kong, where he is now teaching and doing his research, the prospects for promotion are clear. “Here you start off as a student, then you become an assistant professor and then a professor,” says Yakpo. The intervals between the various steps are also standardised. “They don’t have all the intermediate positions and fixedterm contracts that you get in Germany.”

Another thing Yakpo has observed about the German research system is a lack of diversity. Even in African Studies, he notes, the higher the position, the less diverse the appointments – an observation he not only made as a student. As a Humboldt Research Fellow at Humboldt- Universität zu Berlin in 2020/21, he was unable to detect much transformation in matters of diversity in German science.

Listening to Kofi Yakpo it soon becomes clear that he has always found Germany, the country of his birth, too narrow, geographically but also mentally: “Germany is a bit like the European version of the US. People look inwards, not outwards.”

Yakpo was born in Holzminden in Lower Saxony but spent his childhood in Ghana. German is his native tongue. In Ghana he came into contact with his father’s language, Ewe, for the first time. When he was ten, his family moved back to Germany, to Heidelberg, where he taught himself Ewe grammar using an old schoolbook from his parents’ bookshelves. He admits to having been a language nerd. “My first passion was Latin.” Soon he started French and, at 15, was borrowing books on languages from the university library: grammars of Fijian, Tok Pisin, the national language of Papua New Guinea, or Yoruba, one of the three principal languages of Nigeria. “I was under the illusion I could learn any language in no time,” says Yakpo. After doing his civilian service, he enrolled at the University of Cologne to study linguistics.

Hip-hop against racism

On stage, he had already become the “Linguist” by that time. At 17, Kofi Yakpo and four friends had formed the hip-hop group, Advanced Chemistry. With their political texts, the band wrote rap history in Germany. Their song "Fremd im eigenen Land" dealt with contemporary racist structures in the country. A populist public debate on asylum, racial murders and arson attacks in Rostock, Mölln, Solingen and Hoyerswerda were the key topics in society at the time.

“For all the talk of European unity / When I take the bus or train to the border / I ask myself why I’m the only one who has to show ID / has to prove their identity,” rhymed Advanced Chemistry a good 30 years ago. Lines that are just as relevant today. Now as then, social participation has not really embraced migrant communities in Germany, according to Yakpo.

In the mid-1990s, he quit the music scene, started travelling and doing research for his Master’s thesis. His first destination was Vanuatu, an island state in the South Pacific. “I returned to Germany from this trip absolutely euphoric and charged up,” Yakpo remembers. He wanted to continue his research but did not know how. “Doctorate, habilitation – the whole procedure was a bit of a mystery to me.” He would have needed advice, a mentor. But at the time, there was no such person around.

The lack of prospects shattered his illusions – which is why he initially set off in a completely different direction. “Getting away from this narrow Germany,” as he puts it. He studied management and law in Geneva and London, then worked for the human rights organisation FIAN International (FoodFirst Information and Action Network) and subsequently for the Greens at the Bundestag in Berlin.

Today, Kofi Yakpo combines the various elements of his life in his academic work in Hong Kong: instead of hip-hop rhymes, it is now his research results that reveal colonial structures and debunk racist myths.

In Europe language is seen as something that is not supposed to change. In West Africa, it’s different.

One such myth is that Creole languages are simplified languages. Yakpo has managed to prove that many Creole languages are tone languages in which the pitch changes the meaning of a word and the grammar – a concept that is foreign to European languages. “The assumption that Creole languages don’t use a tone system is based on the idea that because we’re not familiar with it, it’s complicated. And because the Africans dragged into slavery couldn’t be ‘complicated’ by definition, Creole languages couldn’t be tone languages,” says Yakpo. Within linguistics, his research field is highly political and controversial. It addresses the colonial legacy and thus often also racist thinking and stereotypical assumptions within his own discipline, which tends to be Eurocentric.

In Africa language is allowed to change

Whilst working as a Humboldt Research Fellow in Berlin, he recently explored another path: “I wanted to know how languages develop when they are not standardised by written forms or state authorities.” After all, strict language standardisation is ultimately a European concept. In Europe, language is seen as something that is not supposed to change. “In West Africa, it’s different,” says Yakpo. “Variation is quite normal.”

Socio-economic aspects are also a feature of his research. Yakpo discovered that participation opportunities and advancement expectations influence the degree to which languages are changed by hybridisation. In this context, he developed the concept of social anchoring. He has demonstrated, for example, that Nigerian Pidgin, which is spoken by 100 to 150 million people today, in all likelihood derived from a small community of Krio-speaking enslaved Africans from Sierra Leone who were released by the British navy from illegal slave transportation off the coast of West Africa and brought to Freetown in the 19th century. “They played a kind of intermediary role between two social classes in what was then a British crown colony and the whole of West Africa,” Yakpo explains. “They were teachers, missionaries and traders with privileged access to the British colonial system and to African society at the same time.” Their enhanced social prestige was an incentive for the majority of Nigerian society to learn their language. “Speakers of the minority language, Krio, had an interest in interacting with the majority population,” says Yakpo.

But this is not always the case – as the history of language and cultural hybridisation in the Caribbean illustrates. “The hierarchy that was created by the colonial system and slavery was so strict that the Africans who arrived in the Caribbean in chains were not the least interested in learning the language of the colonial rulers.” So, says Yakpo, they quickly and radically changed the English language. “A kind of reflex reaction to their lack of opportunities to participate and advance in society.” This finding also contradicts the widely held theory that enslaved Africans in the Caribbean were not capable of learning correct English and, from necessity, had merely simplified the bits and pieces they had picked up and supplemented them with their own languages.

Ultimately, what Yakpo is really concerned with in his research is agency, with Africans’ capacity to act and their resilience, with linguistic research that treats the speakers of Creole languages as acting subjects. In order to conduct this debate within the discipline he is more than willing to battle it out in public with what he refers to as “blingbling linguists” – researchers who try to attract attention by proposing highly-simplified arguments. “I enjoy debates like that,” he says. Here, too, Kofi Yakpo, the Linguist, benefits from his hip-hop alter ego.