Jump to the content

- {{#headlines}}

- {{title}} {{/headlines}}

Professor Dr Martin Wikelski is the world’s leading expert on the global movements of migratory birds, reptiles, mammals and insects. He is a professor at the University of Konstanz and Managing Director of the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology in Radolfzell. After studying and taking his doctorate in Germany, he initially became a Humboldt Research Fellow in the United States, moving via the University of Illinois to Princeton University. In 2008, he returned to Germany to the ornithological station in Radolfzell. Wikelski has had a long relationship with the ornithological station. Aged just ten, he took photos of an invasion of cattle egrets in Bavaria and sent them to Radolfzell. The experts contacted him and introduced him to bird research. Wikelski has received numerous honours, including the 2016 Max Planck Research Award which was granted jointly by the Humboldt Foundation and the Max Planck Society.

A sunny 1 August in southern Germany. On the roof terrace of the ornithological station in Radolfzell it’s boiling hot. The cube-shaped building, part of the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology in Seewiesen, is not far from Radolfzell. The view over the countryside from the roof is amazing – behind the treetops you can positively visualise Lake Constance. Institute staff are taking a break, sitting under an awning and sweating. Ditto the reporter at the next table.

Martin Wikelski, one of the two directors of the institute, is not sweating in the least as he emerges through the door to the terrace, although he would have every reason to do so. Not only because he has just climbed the stairs carrying heavy equipment, but also because his research has now entered the “hot phase”. In two weeks’ time, on 15 August, it will be decided whether the lighthouse project of his department Migration and Immuno-Ecology, the biologist’s life work, ICARUS, will really take off.

“Animals can be our eyes, ears and noses in places we have little chance of getting to ourselves.”

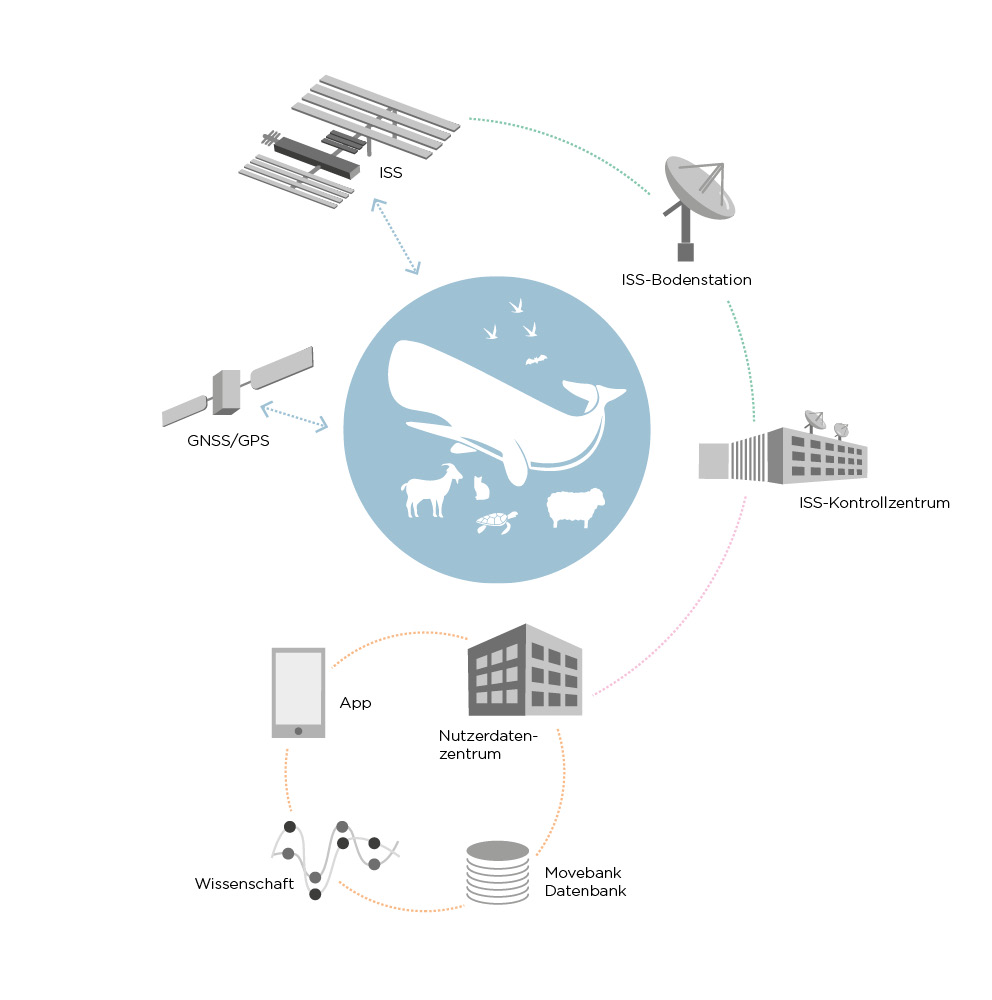

The acronym stands for International Cooperation for Animal Research Using Space. Together with the German Aerospace Center and the Russian Space Corporation, Roscosmos, Wikelski’s team is planning to track animal migration from space, or rather, from the International Space Station, ISS. Normally, migrating birds have numbered rings attached to their feet, for example, so that they can be identified elsewhere at a later date and their migratory paths traced back. Nowadays, researchers prefer to attach wireless tracking devices to the birds to trace their paths more accurately. It can now even be done by satellite. So far, however, conventional satellites have only delivered fairly rough information.

Meticulous tracking

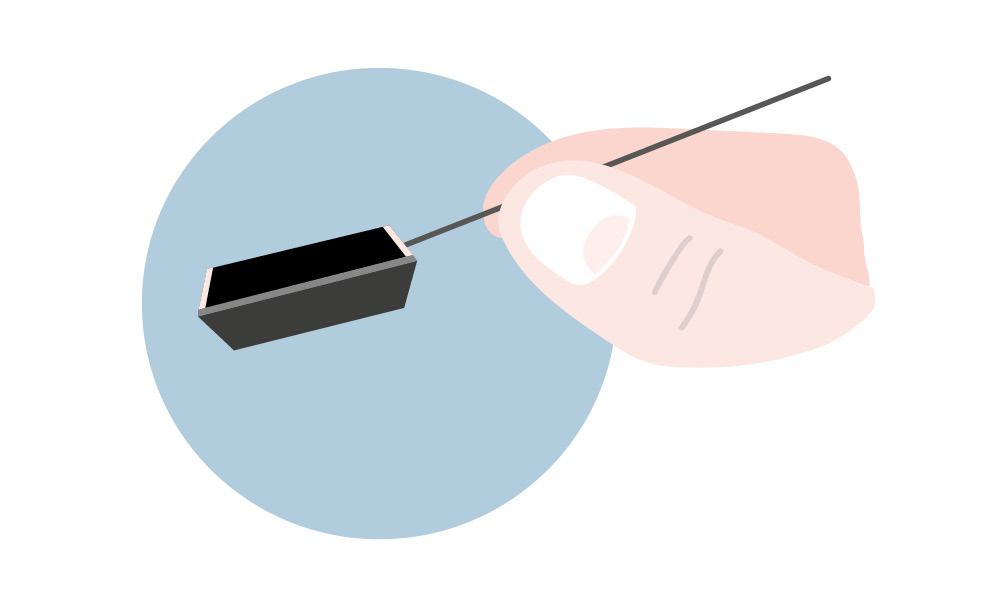

ICARUS is supposed to catapult this so-called animal telemetry, and thus ecology in general, into a whole new dimension. “Our antenna on the ISS will be able to control far more transmitters concurrently, and much more accurately than has been possible so far,” says Wikelski. “And we won’t just collect location data but also data on acceleration, temperature, air pressure, heart rate and anything else we want to measure.” This is all enabled by the miniaturisation of sensor technology. The birds’ trip recorders, known as tags, are currently not much bigger than a thimble and only weigh a few grams. Soon, it will even be possible to tag insects.

Each of the tags has a tiny hard disc which records data for an entire lifetime. “We can track the birds’ whole life history in minute detail with GPS accuracy: when and where they sleep, feed, fight and why they die,” Wikelski explains. His aim over time is to see thousands of animals tagged all over the world. Blackbirds in Europe, for example, in order to discover why some head for wintering grounds and others don’t; domestic cats to check to what extent they really endanger the songbird population; whales and sea turtles to find out how they can be better protected. And the animals are supposed to do us humans a service, too. “They can be our eyes, ears and noses in places we have little chance of getting to ourselves,” says Wikelski. “They can keep us updated on the state of our planet.”

Animals react to pollutants, they quickly reveal an outbreak of avian flu and can register the approach of a devastating swarm of locusts. Indeed, they may even be able to alert us to volcanic eruptions and earthquakes hours before measuring instruments register anything. This is one of the themes Wikelski’s team is currently investigating by tagging, amongst others, sheep and goats on Mount Etna: to date, the animals have always sought shelter roughly five hours before a major eruption – all around the volcano, which means other causes can be excluded. “What exactly they sense, we still don’t know,” says Wikelski. “They have a kind of sixth sense. But their movement patterns clearly indicate their escape behaviour.”

Seventeen years in the making

In other words: tagged animals can provide us humans with a network of highly-intelligent, world-spanning monitoring points and warning devices, and reveal completely new ecological interrelations. “Two hundred and fifty years after the birth of Alexander von Humboldt we can finally realise his vision of a world organism, a holistic understanding of our planet based on its individual parts,” says Wikelski.

All of this – in addition to some 50 million euros in investment – will be at stake on 15 August when cosmonauts will install the ICARUS antenna on the outer surface of the ISS, a procedure expected to take a good seven hours. To ensure that everything runs smoothly, Wikelski and his team will be present at the Russian control centre in Moscow, prepared to answer even the simplest questions. Wikelski first had the idea for ICARUS 17 years ago while he was still doing research in the United States as a 35-year-old. One evening, he was sitting together with the experienced radio astronomer George Swenson. “He said to me, ‘Martin, you biologists have such a colossal topic, super important for the whole of humanity, and you’re still all running around in rubber boots. Think big, get together. We radio astronomers have filled whole valleys with our billion-dollar telescopes and are connected worldwide.’ So, we thought, if astronomers listen in on space to locate the sources of signals, why don’t we simply turn things around and listen in on the Earth from space?” On that evening, the two scientists drew up the basic plan for ICARUS.

At the time, Wikelski brashly predicted that he would have the antenna in place in three years. They turned into 17. Countless obstacles had to be overcome, technological hurdles mounted, funders convinced and disappointments swallowed, for example when NASA or the German Ministry of Research turned him down. For years, ICARUS failed to get off the ground, but Wikelski hauled it over all the hurdles.

“If astronomers listen in on space to locate the source of signals, why don’t we biologists listen in on the earth from space?”

As it happens, “Mr Icarus”, as he is known in the community, nearly dropped out of research even before he had the idea for the project. “Aft er studying and doing my doctorate in Bielefeld – including an extended research trip to South America in Humboldt’s footsteps – I felt the hierarchies in German research were awful.” In the mid-1990s, a friend told him about the Humboldt Foundation’s Feodor Lynen Research Fellowships for German researchers who wanted to go abroad and that there was a behavioural research professor in Seattle, Jim Kenagy, himself a Humboldtian, who hosted postdoctoral fellows. “My application was indeed approved and so I was able to go to America to work on tropical birds,” Wikelski remembers. The Humboldt Foundation, he says, laid the foundation stone for his career.

First results in 2019

During the time he spent in the US, Wikelski made a name for himself as an animal migration researcher. The elite university, Princeton, awarded him a lifetime professorship. Nevertheless, when he was offered the chance to return to Germany in 2008, he accepted, disillusioned by NASA’s rejection and the Bush administration’s hostility towards science.

Time shift. It is the beginning of September: the ICARUS antenna has been successfully installed – even the German news flagship Tagesschau reported on it. “Everything has gone brilliantly,” says Wikelski on the phone, “even though it was really stressful.” The first data are scheduled to flow in in the winter; the first results are expected in 2019. Wikelski is extremely satisfied. Longtime colleagues like Kasper Thorup, a zoologist at Denmark’s Natural History Museum in Copenhagen who has worked with Wikelski for ten years, admire his perseverance. “I have little doubt that ICARUS will now transform biology and ecology in particular.”

Modern animal telemetry has already jettisoned much of what was received wisdom in research on specifi c species and ecological interrelations. “ICARUS will dismantle a load of other dogmas, too,” Wikelski is convinced. He now plans to recruit financially strong partners to expand the project and install additional antennas with satellites in space. By making animal observation from space more continuous, the aim is to gain a deeper understanding of the processes in nature. Global institutions like the World Health Organisation and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have already signalled their interest. “Although,” says Wikelski, “the best ideas about what we can do with ICARUS are actually yet to come.”

aus Humboldt Kosmos 109/2018