Jump to the content

- {{#headlines}}

- {{title}} {{/headlines}}

Professor Dr Myles W. Jackson is a faculty member of the School of Historical Studies at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, USA, where he is also a Professor of Science History. In 2014, the Humboldt Research Fellow received the Reimar Lüst Award, which is jointly granted by the Humboldt Foundation and the Fritz Thyssen Foundation up to twice a year. Jackson has received many prizes and honors and is a member of numerous international bodies in countries like the United States, Belgium and Germany, including the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina in Halle (Saale).

Wunderbar Together

Visit www.wunderbartogether.org for information on The Year of German-American Friendship 2018 / 2019

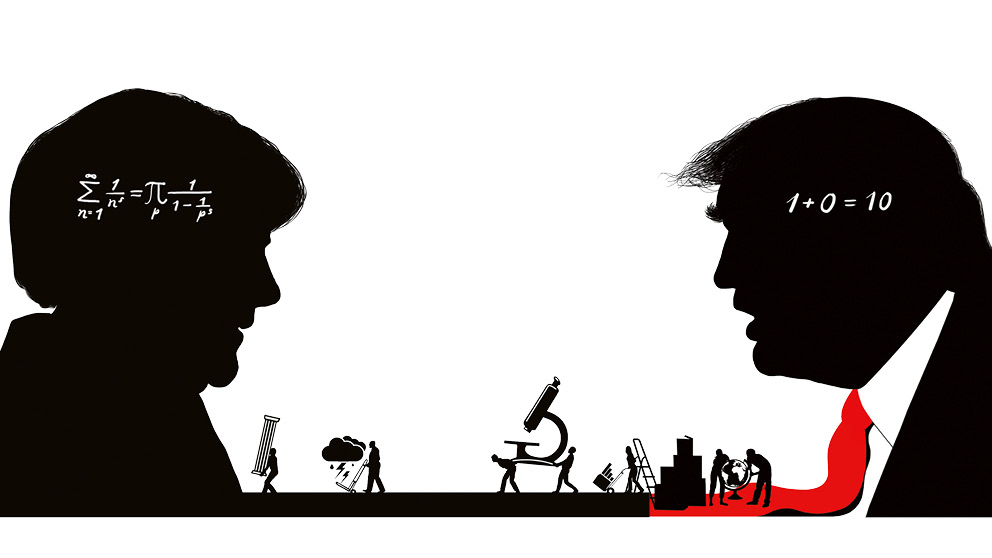

I admire and applaud the decision of Germany’s Foreign Office to declare 2018-19 “The Year of Germany” in the United States. The promotion of rational, intelligent dialogue and exchange stands in sharp contrast to Donald Trump’s current hurling of insults at Germany. During this period of global anti-intellectualism the res publica litterarum must stand above the petty and treacherous politics of nationalism in order to encourage international exchange.

In the last decade, I have observed a fundamental change in the attitude of my academic colleagues to Germany. My first extended visit to Germany was in 1983. I was just 18 and an academic assistant at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Martinsried, near Munich. Since then, I’ve frequently been to Germany, most recently for a whole year to the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin.

Nobody understood my infatuation

In the 1980s, 90s and early 2000s, my colleagues couldn’t understand why I was so – what they saw as – infatuated with Germany. They thought it highly suspicious that someone who didn’t have German ancestry spent so much of his time learning the language and studying German culture and history. I constantly had to justify myself, particularly to my Jewish colleagues, some of whom told me they would never set foot in Germany.

Today, I no longer need to explain why I chose Germany as the object of my research. I have also spoken to plenty of Jewish colleagues who are now quite positive about Germany and often travel there.

While Angela Merkel’s willingness to accept refugees is contentious in Germany, a large number of U.S. academics have applauded her for it. Many of us praise the Chancellor for her central role in trying to stabilize relations between the U.S. and Germany in such a turbulent phase of our history. She is often described here as the leader of the free world.

Germany’s reputation among academics in the U.S. has enhanced enormously. An increasing number of them are actively looking for ways to work in Germany. And academic cooperation between Germany and the U.S. really could be an effective antidote to the rhetorical blustering currently blighting Washington.

Macron is also rolling out the red carpet

Given the present political climate, many of us are deeply concerned about the future of U.S. academic institutions. Will there be a brain drain in the United States if the current climate persists? Historians are generally hesitant to make any prognostications; however, early indications suggest that an exodus is possible. It wouldn’t surprise me. At the end of December 2017, the first phase of French President Emmanuel Macron’s goal to entice climate scientists to come to France was very successful: 13 of the 18 scientists awarded scholarships (among them several French nationals) had been working in the United States before Macron’s initiative brought them to France. Similarly, Germany is attracting top researchers working in the United States with its Alexander von Humboldt Professorships. I was greatly honored to be offered one of them, and it was no easy decision to turn it down. It was only because I was offered a professorship at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton at the same time that I decided not to uproot myself and head for Germany.

“Given the political climate, will there be an exodus of academics from the U.S.?”

In the first decade of the program, nearly half of the researchers who accepted an Alexander von Humboldt Professorship at universities in Germany came from the United States. Given the current U.S. administration’s contempt for academic scholarship, coupled with Germany’s conducive atmosphere and generous support for research, there is a very real chance that these figures will rise. I personally think that younger U.S. scholars are far more likely to take advantage of the resources provided by Germany and the European Union. Encouraging young researchers in the humanities, social sciences and natural sciences to spend time on research in both the United States and Germany would certainly facilitate a rich exchange of ideas between the two countries.

We could learn a lot from one another

We Americans are good at interdisciplinary research and teaching. We are often much more creative when it comes to crossing the boundaries between research areas. In Germany, on the other hand, the rigid definition of disciplines should be broken down more often. Universities here frequently base their future planning on past needs and miss the opportunity to re-design their fields of work.

Most of us have come across the bureaucratic reputation of German universities that are thought to nip creativity in the bud. But there are also conservative faculties at American universities that are intent on carefully safeguarding their interests. A number of universities have adopted a cluster strategy for appointments whereby colleagues from different disciplines cooperate on a certain topic. Take human classification, for example. Here you could appoint researchers in molecular biology, sociology, anthropology and history of science. Then you establish new interdisciplinary programs which benefit both the relevant field of work and the students. Such appointments are often privately funded by organizations like the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Germany has introduced a similar initiative with the German Research Foundation’s Collaborative Research Centres. It is of course difficult to develop a measurement method to determine the success of such programs, but this kind of flexibility in research and teaching does make sense if you want to respond to new challenges.

Challenge: genetic research

Another area with ample scope for knowledge sharing is how to handle genetic research. It confronts societies with existential questions that are posed differently in the two countries. In the United States, the question asked is: can one ascertain the ‘race/races’ of an individual from her DNA? What are the implications if one can, for example with regard to the issue of how different diseases affect different populations?

“Cooperation between academics is an effective antidote to the rhetorical blustering blighting Washington.”

For many researchers, the field of race and genomics is about redressing the sins of the U.S. medical community’s past, such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, where African-American men were purposely not treated for syphilis between 1932 and 1972 in order to study the long-term effects of the disease. Today, studying race is no longer essentially about exclusion as it was in the past, but inclusion. Data are needed on the safety and efficacy of drugs for women and people of color: the white male has served his purpose as a universal research subject for health issues.

Another area of research is genetic privacy. Germany has very strict data protection laws. Again, this is a product of its past. Does this hamper the sharing of information for research? A number of biomedical researchers in Germany claim that it does. The United States, on the other hand, is much more relaxed about information sharing. Despite the restrictions set in place by the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) of 2008, personal genomics companies share the anonymized data of their clients with third parties, including Big Pharma and insurance companies. Personal genomics companies, such as 23andMe, AncestryDNA, and FamilyTree, advertise directly to U.S. consumers who wish to find out about their ancestry.

Germans do their genetic testing in Switzerland

The story is somewhat different in Germany, which has clearly had a checkered history with race and genetics during the Third Reich. Nevertheless, genetic testing is gaining in popularity among Germans; interestingly, the analyses are undertaken in laboratories located in neighboring countries, such as Switzerland, and the results are then sent back to the clients. Germans are generally interested in genes associated with lifestyle and nutrition; questions about race and ethnicity are taboo. I think it’s no exaggeration to say that Germany spends more time thinking about its past and about the ways that past impacts the present than any other country. Vergangenheitsbewältigung, that wonderful German word for the process of coming to terms with the past, always plays an important role when Germany attempts to resolve moral issues and make political decisions. Germany and the United States are both actively involved in the debates about CRISPR / Cas9, a new method that can edit genomes with unprecedented precision. The conversation between the two countries may help them to find the right balance between scientific innovation and ethical boundaries.

aus Humboldt Kosmos 109/2018