Contact

Press, Communications and Marketing

Tel.: +49 228 833-144

Fax: +49 228 833-441

presse[at]avh.de

Jessé Souza is a fellow of the Philipp Schwartz Initiative, conducting research at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin on suffering under global capitalism. In close collaboration with his colleague and host, the Berlin sociologist and globalisation researcher Boike Rehbein, he investigates how socio-economic structures and social exclusion processes are interlinked. But neither researcher is satisfied with just exploring people’s life situation. Particularly in the Global South, they want to create opportunities for participation and offer people low-threshold, affordable access to quality education. To this end, they have started an online school for people in need. The model has already been implemented successfully in Brazil. Recently, another school project was launched in India.

Humboldt Foundation: In your research, you both cite education as an important factor in inequality. What role does it play?

Boike Rehbein: When considering education, we first of all have to differentiate between two aspects: training and education. All over the world, we see training as a decisive factor in replicating social inequality. People who grow up in a disadvantaged situation don’t usually have the chance to acquire higher, or higher quality, qualifications. And if they don’t have these qualifications they are excluded from most privileged positions, functions and even activities in society. On the other hand, we observe that inequality structures in education itself are not addressed sufficiently. We learn individual factors about society, but we don’t understand how everything hangs together. Both factors are important to us: a better understanding of the social world and compensating certain disadvantaged groups in the population for structural disadvantages.

Jessè Souza: If you want to understand the structural problems it’s particularly important to examine the relationship between the Global South and the Global North. Today’s exploitive relationships are often regarded as deriving from the Global North’s supposed cultural and moral superiority, which legitimises and facilitates the economic exploitation of the Global South. There is an intrinsic connection between poverty and the kind of deep-seated racism, both at national and global level, that leads to people being left behind.

At the same time, you say that the causes of inequality are not just economic.

Rehbein: Most of all, it has a lot to do with self-esteem. The image that the rest of society has of the lower classes is that they are “trash”. We have done thousands of interviews. And this term crops up time and again. We heard it in conversations with homeless people in Germany but also in Brazil. It is adopted by the people themselves. They internalise the way they are judged by the rest of society. That is the main marker of the underprivileged. They don’t dare to carry out a certain function within society or to behave as equals. This is where we need to start.

How did you come up with the idea to open an online institute?

Souza: We were always talking to one another and asking ourselves how we could utilise our findings beyond the narrow confines of academia. How can you convey social criticism to the people who need it most? And so, we looked for support – locally. In Brazil, the school is already successful and now we are going to implement the idea in India.

How did you set up the school? Who is involved locally?

Souza: In Brazil, we have the support of social movements, above all the Landless Workers, but also Black and Catholic initiatives. One year on, we have more than 30,000 students. Those who can afford it, pay roughly eight euros a month. In India, the fee is one euro. And for that the students are taught by the best minds in the country – internationally, too – in politics, social science and history. People are given a new interpretation of the social situation in Brazil that is not on offer anywhere else. And they can acquire so-called hard skills at the same time. They learn foreign languages and can take part in professional courses that prepare them better for employment. We have scholarships for those who can’t pay, financed by the local social movements. The poor deserve the best.

How does the school work in practice?

Souza: The courses are all online. That is cheaper, and we can concentrate on conveying knowledge. To do so, we invest in producing web documentations which, again, are created by the communities, by the people themselves. We provide the material so that the people can organise everything autonomously. They are not supposed to be passive learners.

But not everyone has a computer. How low is the threshold for people to participate?

Souza: We provide local support, too. As part of a research project in the favelas we set up a room with computers and free internet. Also, in Brazil, nearly everyone has a mobile phone, even the poorest people.

Rehbein: In India, we are using an app from the word go. You certainly can’t assume that everyone has a computer. We have teams in Brazil and India who advise us on IT infrastructure and provide support. We also try to offer training sessions to increase people’s ability to concentrate, to focus, or to boost their self-confidence, all conducted by trained social psychologists.

Thanks not least to support from the Humboldt Foundation, the two researchers have been holding a productive conversation on social inequality and the socio-economic interconnections between the Global North and the Global South for the last 15 years. In 2014, they jointly published the book Inequality in Capitalist Societies.

What has motivated you to stick with it the whole time?

Souza: Without the Humboldt Foundation, it wouldn’t have been possible to keep up the momentum. And Brazil has shown us that it can work. It remains to be seen whether the school can help to change the political situation. But we must make people aware of the structural problems, sensitise them to inequality and also reinforce their competencies. I think that is the major challenge: to create a critical social science for today that thinks globally. With solidarity and human kindness – which are also part of science.

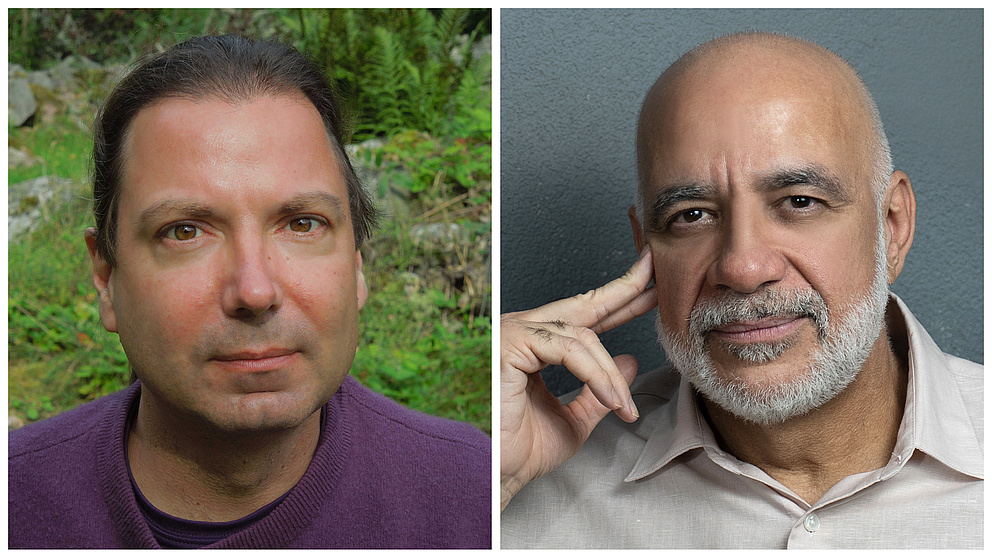

Boike Rehbein studied philosophy, sociology and history in Freiburg im Breisgau, Paris, Frankfurt am Main, Göttingen and Berlin. He was head of the Global Studies Programme at the University of Freiburg before relocating to Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin where he is Professor of Society and Transformation in Asia and Africa. He works on the theories and effects of globalisation with a focus on Southeast Asia. Boike Rehbein is one of the leading experts on Laos and the sociology of Pierre Bourdieu.

Jessé Souza studied law and sociology at the University of Brasilia and Heidelberg University. He completed a postdoctoral course in philosophy and psychoanalysis at the New School for Social Research in New York and acquired his habilitation in sociology at Europa-Universität Flensburg. Souza was a professor at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora in Brazil and head of the Center for Inequality Research located there. In 2019, he held a visiting professorship at Sorbonne University in Paris. Jessé Souza was a Humboldt Research Fellow and is currently a fellow of the Philipp Schwartz Initiative at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. His research focuses on social inequality as well as class and social theory. He is one of Brazil’s most well-known sociologists.