Jump to the content

- {{#headlines}}

- {{title}} {{/headlines}}

Many academic disciplines only actually developed and established themselves at the height of colonialism in the 19th century,” says Ulrike Lindner, historian and expert on imperial and colonial history. Colonial history, the history of knowledge and the history of science, she maintains, are now inextricably interwoven. Geography, for example, with its measuring projects and cartography was the basis of later military campaigns. Biology benefitted from the study of plants and animals that were collected in the colonies. And disciplines like ethnology and anthropology would never have come about in the first place if it were not for colonialism.

On their expeditions to the colonies, European adventurers, traders and scientists collected countless items and brought them back to Europe – from rock samples to cultural artefacts, from everyday objects through to human beings who were exhibited in human zoos in Europe. Quite often, the aim of these collections and research was to underpin the supposed superiority of western societies. “Ethnology, for instance, collected objects on the assumption that other cultures were inferior,” explains Ulrike Lindner who conducted research at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom in 2005 supported by a Feodor Lynen Research Fellowship. “And many anthropologists wanted to use skull measurements to prove that people in non-European societies were more primitive and less intelligent than Europeans. At the time, this was hailed as science. In today’s understanding, it’s racism.”

Eurocentric assumptions – often, but not always of a racial nature – not only shaped European discoverers’ passion for collecting; they also found their way into travelogues, biographies and history books where a certain type of narrative dominated: “How exploration of the world was presented was often shaped by the topos of the European or American man driving research, development and progress as a whole,” explains Moritz von Brescius, historian and expert on European overseas journeys of discovery at the University of Bern who is currently working at Harvard. “The image of these great European discoverers heading expeditions against hostile nature and allegedly hostile natives in order to carry the flame of the Enlightenment into unknown parts of the world does not correspond to the truth.”

Indispensable knowledge

Von Brescius has conducted particularly intensive research on the expeditions of the Schlagintweit brothers from Munich who set off for India and Central Asia in the mid- 19th century, supported by Alexander von Humboldt. “Sometimes they had more than 50, or even 100, people accompanying them: local porters, guides, translators, cooks, hunters. They all had indispensable knowledge about things like mountain passes, springs and medicinal plants.” Usually, the leaders of the European expeditions did not speak the languages of the regions they were visiting and thus depended on their Indigenous attendants in many ways. But that was rarely mentioned in travelogues or was deleted during publishing history – for various reasons, such as racist resentment and the cultural limitations of what could be said at the time as well as attempts to increase the books’ sales figures by means of clichéd descriptions.

Moreover, the Europeans seldom had to explore “the wild” on their expeditions as the accounts sometimes suggest: travellers to Africa, for example, could utilise existing infrastructures with teams of porters and caravan routes. In India, European travellers on some routes could stay comfortably in hotels. “Of course, this contradicts the image we have of overseas expeditions,” says von Brescius. “When we are talking about discoveries, we simply have to always ask ourselves: discoveries for whom?” What was new to European travellers was usually only too familiar to the people in the region and they were often willing to share their knowledge.

“Western science has long been reliant on the knowledge and the exploitation of colonised peoples.”

“Local people showed the conquerors natural medicinal plants, for example. This led to scientific insights that were used to develop medicines,” explains Marleen Haboud. She is an anthropologist and founder of the Oralidad Modernidad Interdisciplinary Research Programme at the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador. A sociolinguist, she studies Indigenous languages. “So, Western science has long been reliant on the knowledge and, indeed, the exploitation of colonised peoples.”

Loss of culture

The consequences for colonised people were and are serious. To this day, many Indigenous people are ashamed of their roots, reports Haboud, a Georg Forster Research Award Winner. “In the colonial context, Indigenous peoples were looked upon as non-human beings without a soul. Their languages were considered useless. To this day, many Indigenous people don’t bother to learn their ancestral language and try to resemble Spaniards and city dwellers.” Colonial legacies of this kind can be observed all over the world and not only endanger Indigenous people’s success in life but also cultural diversity. “Fifty percent of the approximately 7,000 Indigenous languages worldwide are seriously in danger of dying out in the next decade. That of course means that not only the languages get lost, but also unique knowledge, unique practices and traditions,” explains Haboud.

“Much of people’s own culture is forfeited and there is a lack of appreciation of their own culture,” is also the view of the historian Ulrike Lindner. One result was that opportunities to understand their own culture were wasted. Consequently, many cultural and historically significant artefacts have remained in Europe right up to the present. “Europeans don’t have to travel to Africa to look at paintings by Rembrandt. But many Africans have to come to Europe to see objects and cultural heritage from their own countries.” One example: the famous Brachiosaurus skeleton in the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin that comes from Tanzania. “In Tanzania, several things of this kind were discovered. Today, there are hardly any left in the country,” says Ulrike Lindner. “This reflects the imbalance of power between Europe and the former colonies and perpetuates it at the same time.”

According to Marleen Haboud, even now, Indigenous knowledge is often not valued but seen through the lens of colonial history. Her criticism concurs with Ulrike Lindner’s observation that structures and practices from colonial times still exist – in academia, too. “To this day, research projects in countries in the Global South often gather things together that are then exploited in the United States or Europe. I think doing this kind of groundwork in generating knowledge is also a consequence of colonialism.” In the last two decades, however, a change in consciousness could be observed. European researchers were becoming increasingly self-critical, reflecting on the sciences’ colonial heritage. Moreover, countries in the Global South were becoming more self-confident, restricting access to their resources and demanding participation in research projects. Colonial history was now also painting a more differentiated picture than it had for a long time. But the process of reflection is still far from over.

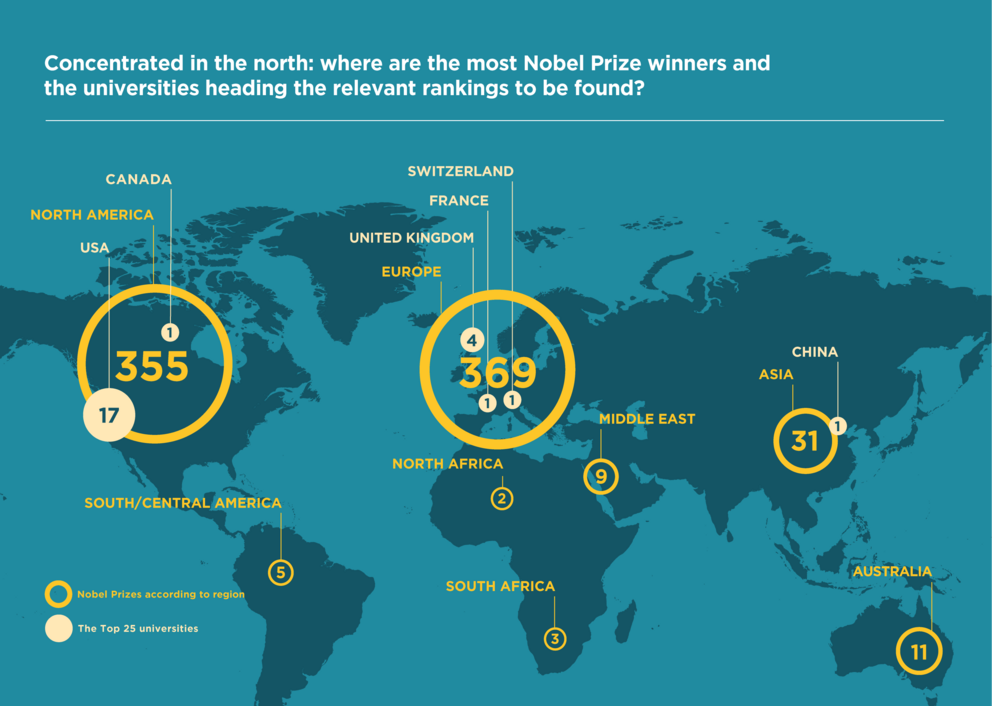

Excursion: Distribution of Nobel Prize winners and top universities according to region

Nobel Prizes according to region

This map summarises the Nobel Prize winners in chemistry, physics and medicine/ physiology as well as the holders of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences according to region of origin as of 2023. Known as the Nobel Prize in Economics, it has been awarded by the National Bank of Sweden since 1968. Overall, the so-called Global North is clearly dominant. Too little diversity in selecting prize winners is one point of criticism recently levelled against the traditional prizes, whether in relation to gender distribution or regional and ethnic origin.

The top 25 universities

This map presents the regional distribution of the universities that took the top 25 positions in the 2023 Academic Ranking of World Universities. Here, too, the Global North is dominant; only China has a university in the top 25. Known as the ShanghaiRanking, it is one of the best-known international rankings and compares publications, citation rates and prestigious awards. The credibility and methodology of such university rankings comes in for considerable criticism. But they are still very influential in the international locational competition as well as the distribution of public research funding

Sources: Nobel Prizes: based on Statista.com. Due to different geographical allocations, deviations may occur in comparison with other sources.

Ranking: www.shanghairanking.com/news/arwu/2023