Jump to the content

- {{#headlines}}

- {{title}} {{/headlines}}

For years, one assumption about the global science system seemed to be set in stone: relevant, path-breaking research with its analyses, discoveries and innovations that would decisively advance humanity was only taking place in the high-income countries of the Global North. In countries of the Global South with low and medium incomes, on the other hand, for just as many years, the results of these outstanding scientific achievements were at best consumed. But is this really the case? How (un)fair is the global science system?

If we take a look at the international academic landscape, a fairly clear picture emerges: To this day, North-American Ivy League universities and European elite universities head the relevant rankings. With their reputations as centres of excellence, it is much easier for them to attract outstanding researchers – who then do yet more excellent research when they get there. On the other side, there are universities, in Sub-Saharan Africa for example, which can often not even finance the purchase of the basic equipment needed to conduct significant research. The editorial offices of leading science journals have also traditionally been located in Europe and North America. With the help of peer reviews and a selection policy geared to the Global North, they are partly responsible for deciding which research, which knowledge and what form of knowledge acquisition are seen as the gold standard.

In focus: Postdocs in Africa

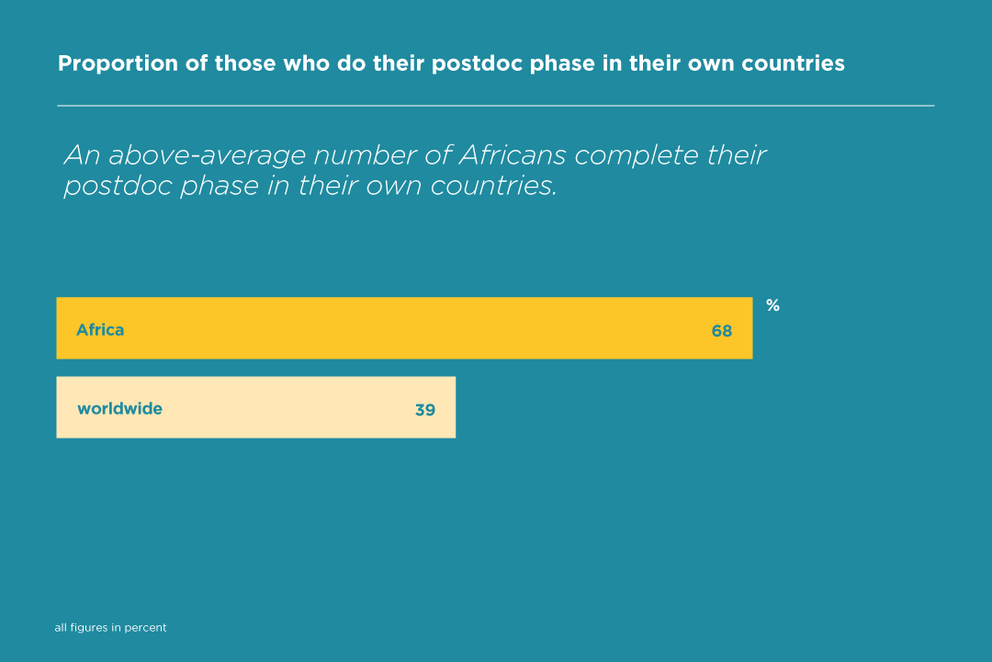

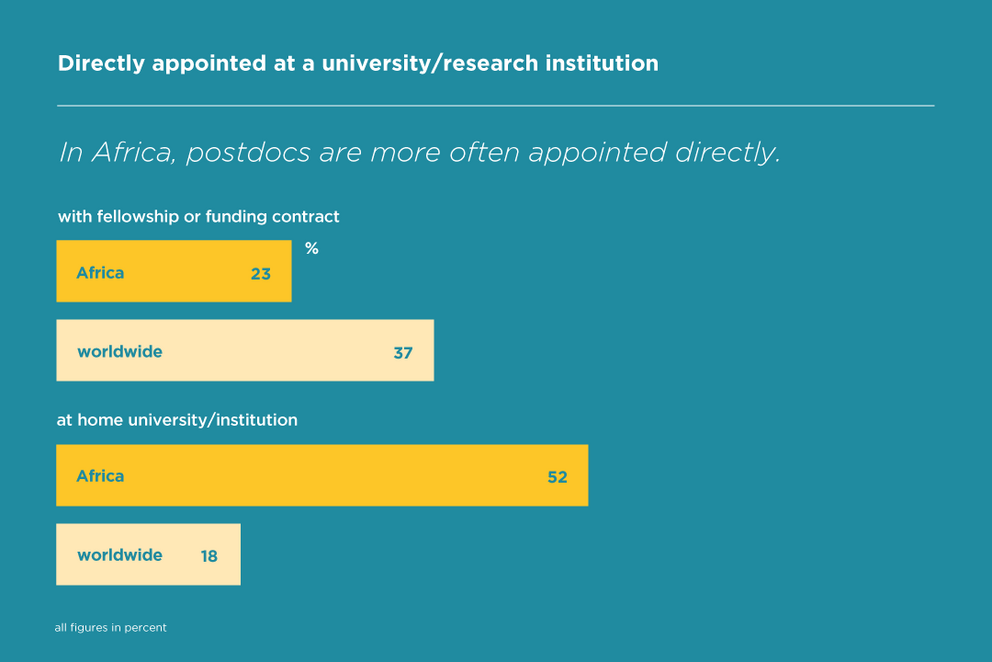

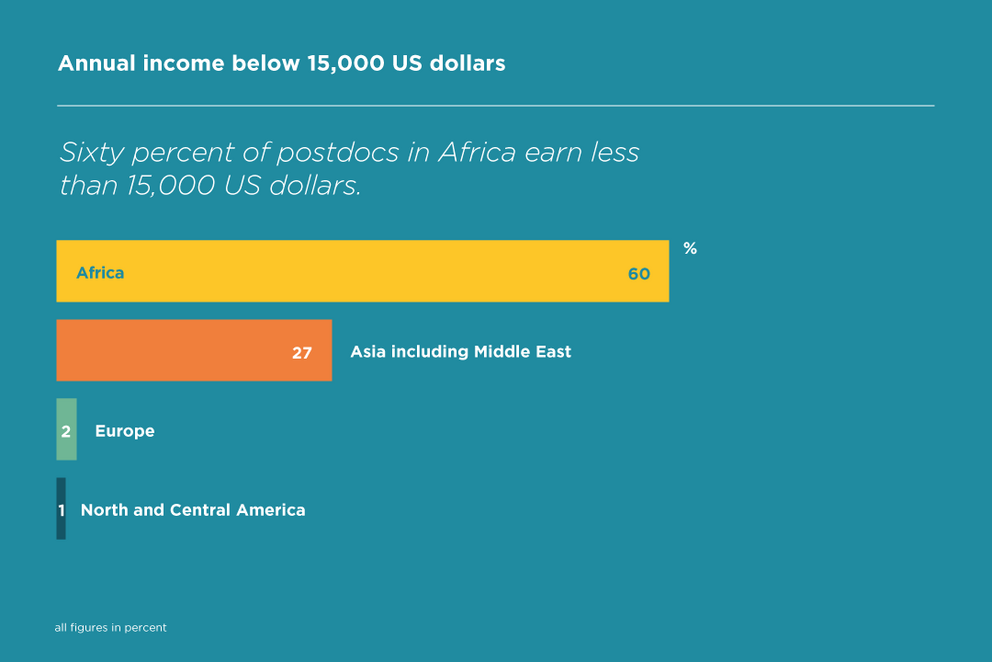

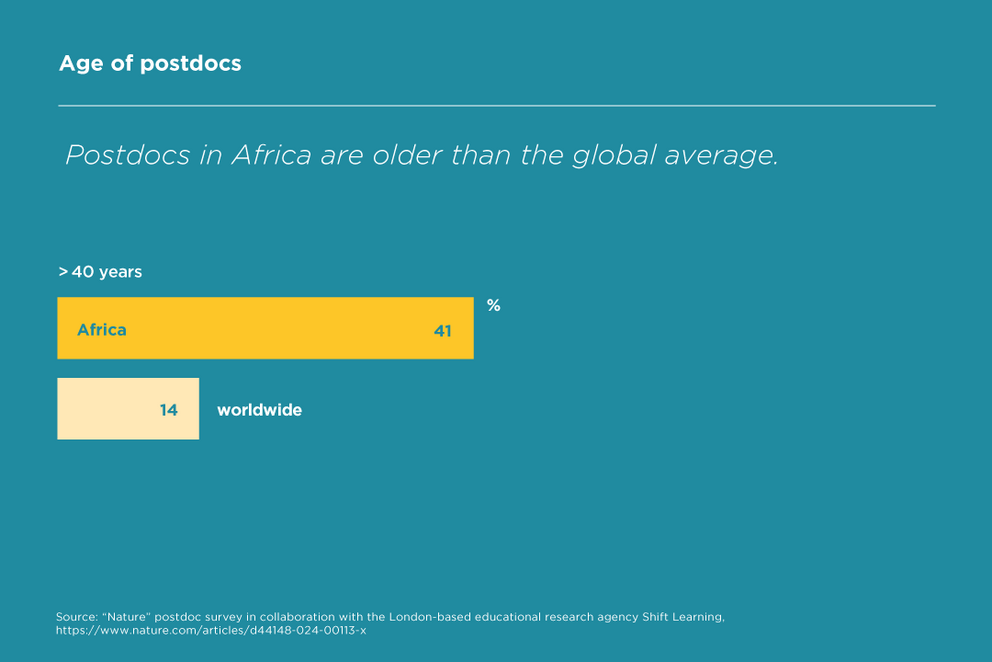

In Africa, too, ever more students are studying for doctorates. By analogy, the importance of and need for postdoctoral positions is growing – a challenge for African countries’ science systems. The figures are taken from a survey conducted by the journal “Nature” in 2023. It gives new insights and reveals trends but is not considered representative. Of the 3,838 postdocs surveyed, only 91 were living on the continent and they mainly came from South Africa, Nigeria and Egypt.

Source: “Nature” postdoc survey in collaboration with the London-based educational research agency Shift Learning

Unequal distribution

“Both the resources and the infrastructure within the global knowledge production system are unfairly distributed,” says the legal scholar and science theorist Sheila Jasanoff who established Science and Technology Studies as a subject at Harvard University. “What is relevant here is not only the amount states invest in science per head of the population but also secondary factors like the computing capacity of the IT systems researchers are able to use.” This, in turn, depends on whether there is a stable power supply in the respective country. “Factors like this that are run of the mill in some parts of the world determine who cooperates with whom and whether cooperating researchers in different locations can discuss a relevant question in a video call without technical hitches,” explains Jasanoff who received the Humboldt Foundation’s Reimar Lüst Award in 2017.

“We need a new era of innovation in our thinking about science.“

She is therefore calling for far-reaching change. “We often say that innovations spring from science,” she says. “I think we really need a new era of innovation in our thinking about science.” This would include recognising that the metrics and concepts used to measure progress and excellence are not free from colonial legacy. “What we need is not an African CERN,” says Jasanoff, nor the hierarchical thinking behind such a demand. “We must understand that as well as the natural sciences so highly esteemed in the Global North, there are other concepts of knowledge and knowledge production that are equally relevant and worth promoting.”

One institution that has already recognised this is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (ICCP) which now welcomes Indigenous knowledge in the fight against climate change. But Jasanoff criticises the fact that referring to Indigenous knowledge is also evidence of thinking shaped by westerntype pigeonholing and hierarchical thinking. “People in the West don’t think of themselves as ‘Indigenous’ because they associate this knowledge with ‘primitive’,” she explains. “We have to accept that knowledge is more comprehensive than what is generated by researchers in their labs or in mathematical models – and that it doesn’t necessarily hail from universities.”

Developments in Artificial Intelligence (AI) worldwide

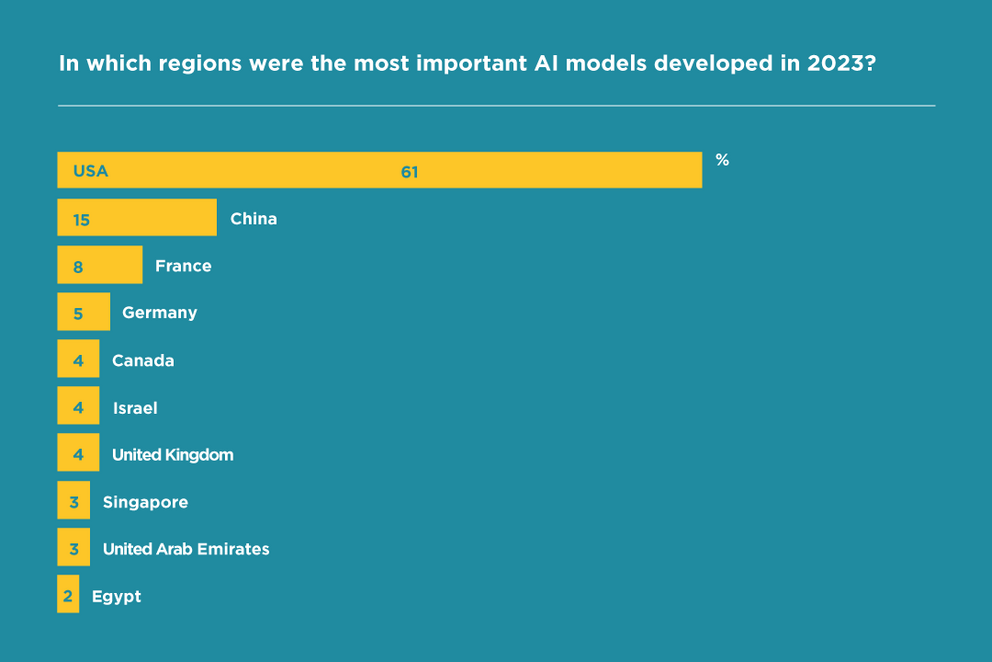

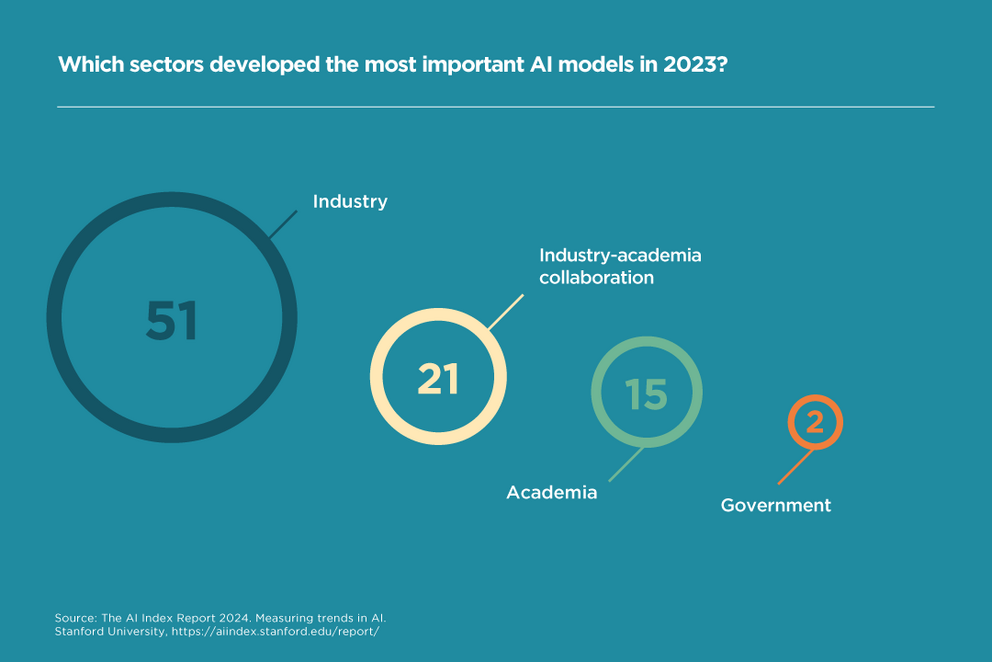

Today AI is seen as an indicator of innovative strength. Stanford University’s AI Index Report gives a worldwide overview of developments in artificial intelligence (AI). The 2024 report examines technical progress, public perception of AI and geopolitical developments, for example in which countries and sectors the most AI models have been developed. This reveals a broader global distribution of countries – and industry lies well ahead of research in academia – which may partly have to do with the costs involved, particularly in training these models, as the study shows.

Source: The AI Index Report 2024. Measuring trends in AI. Stanford University

Robbed of their humanity

Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Professor and Chair of Epistemologies of the Global South with a focus on Africa at the University of Bayreuth and Humboldt Foundation academic host, also argues thus. “At the beginning of the modern era, people were racialised and anyone who wasn’t white was robbed of their humanity according to the gradations of their skin colour,” he says. “People who are thought of as belonging to a subcategory of human beings are neither permitted a history, nor knowledge, culture, or language.” Applied to the problem of climate change, for instance, this means that “anyone who does not believe in technological progress but sees themselves as part of living nature in which trees, rivers and mountains are also living creatures, is considered barbaric and in need of civilising,” says Ndlovu-Gatsheni. Given the complexity of the challenges facing humanity, he calls upon people to “dare to fundamentally question everything we have believed so far and to embark on a process of unlearning certainties.”

“Good intentions alone will not break down established power structures.”

Excellent south

To this end, it would be necessary to turn away from the knowledge hubs in highincome countries, says Sheila Jasanoff. “Young, internationally mobile researchers from the Global South have nearly all studied in North America and Europe,” she says. Young researchers from the Global North taking degrees in the Global South, on the other hand, was a rare occurrence, although it would be theoretically possible to provide excellent education in the countries of the Global South – at a fraction of the cost of Ivy League universities. Jasanoff refers to “frugal science,” an Indian concept whereby capital and material usage are kept as modest as possible. “What makes science frugal whilst it can still be called science is actually a scientific question that should be explored,” she says.

Daya Reddy observes similar developments in Africa. The emeritus Professor of Applied Mathematics at the University of Cape Town and former President of the International Science Council is the chair of the Humboldt Foundation’s International Advisory Board. “Regional hubs have been developing for a long time,” says Reddy and cites the Alliance of Research Universities in Africa (ARUA) as an example: an African network of currently 23 particularly research-intensive universities. “At my university, too, 15 percent of the students come from other African countries because the quality of the education we offer is so high,” he says. In order to establish and reinforce such regional science hubs, research collaborations with researchers in the Global North are essential, he says. “This is the only way universities in the Global South can become attractive destinations for studying.”

“Power and Knowledge – confronting global imbalances in our knowledge systems”: the 2024 Humboldt Residency Programme involving eleven international participants from academia, the media and civil society also addresses the challenges of and new paths for global knowledge transfer.

Above all, Reddy believes international academic institutions have a duty to promote an equitable global research landscape. “The criteria for awarding research funding must be designed in a way that would create fair North-South academic partnerships and not helicopter science where data are collected by researchers in the Global South who are, however, not equal partners,” he says. Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni initially wants to address the topic of an even playing field theoretically before starting to develop solutions. “First of all, we have to know exactly what problems we are dealing with,” he says. “Good intentions alone will not break down established power structures.” The key question is, “How can we ensure that all the knowledge that reflects the diversity and plurality of humanity really gets a hearing?” Currently, there are many approaches and ideas that should be combined. “None of us has a ready answer to how a fair science system should be designed,” he says. “But in the process of unlearning certainties, upon which we must all embark, a path will emerge.”