Jump to the content

- {{#headlines}}

- {{title}} {{/headlines}}

Kharkiv, Ukraine, February 24, 2022: Russian missiles destroy the Faculty of Physics and Technology at Vasyl Karazin National University. Through the PSI Emergency Fund Ukraine and its participation in the EU program MSCA4Ukraine, the Humboldt Foundation supports targeted measures to provide rapid assistance to Ukrainian researchers who have fled their home countries. (Title photo)

Philipp Schwartz Initiative – Protection for threatened researchers

They are some of the thought leaders in their countries. But they cannot continue their research there. “These people do impressive work,” says Judith Wellen, head of the Humboldt Foundation’s Strategy and External Relations Department in which the Philipp Schwartz Initiative is embedded. “But then war and violence destroy universities and labs. Others are oppressed, experience discrimination or abuse – because of their gender, ethnicity, sexual identity or because they voice criticism.”

Since it was established in 1953, the Foundation has repeatedly supported researchers who were under threat or subject to political persecution in their own countries – whether during Apartheid in South Africa or in the Cold War years. It was not least due to this extensive experience, says Wellen, that the Foundation started grappling with tailored opportunities for researchers in such situations.

Programme sending a signal

In 2015, the mass exodus from Syria and other crisis regions was the trigger for a targeted programme. “We wanted to find ways of giving the researchers affected a perspective so that they could continue their research and conserve their knowledge,” Wellen explains.

With the support of the Federal Foreign Office, the Foundation launched the Philipp Schwartz Initiative (PSI) and in 2016, the first sponsorship recipients embarked on their fellowships. At the time, this kind of initiative was unique in Europe, but it soon became a template for other programmes. With its Philipp Schwartz Initiative, the Humboldt Foundation is now one of the most important actors worldwide in the protection of researchers at risk and is active in EU projects such as MSCA4Ukraine, Inspireurope and SAFE.

First impressive results from the Philipp Schwartz Initiative

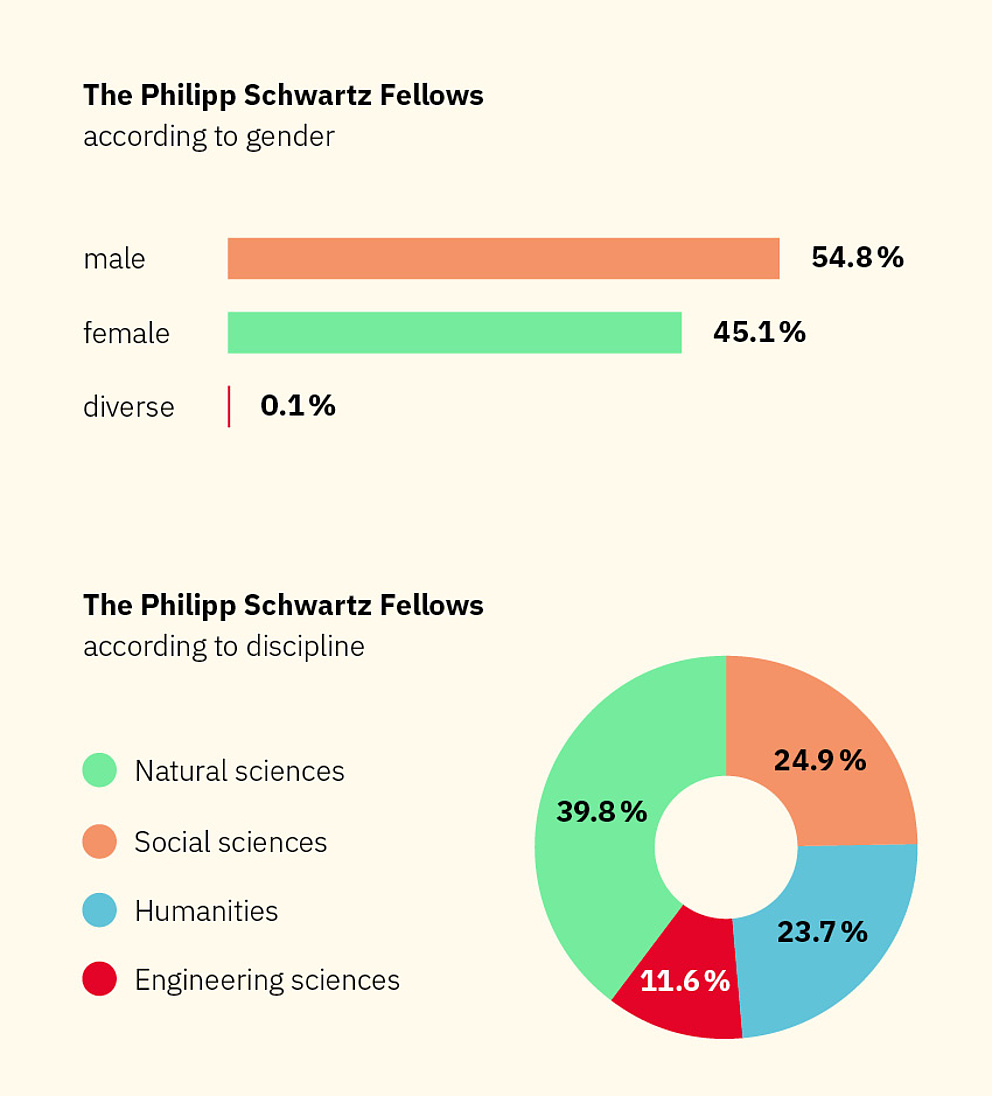

To date, 674 at-risk researchers from over 30 countries (as of December 2025) have found a new scientific home in Germany, including through special programmes for researchers from Ukraine, Afghanistan and Iran that the Foundation introduced together with the Federal Foreign Office at short notice in response to geopolitical developments and trouble spots.

(*under the main PSI programme, not including bridging fellowships and the Ukraine Emergency Fund)

All data as of December 2025.

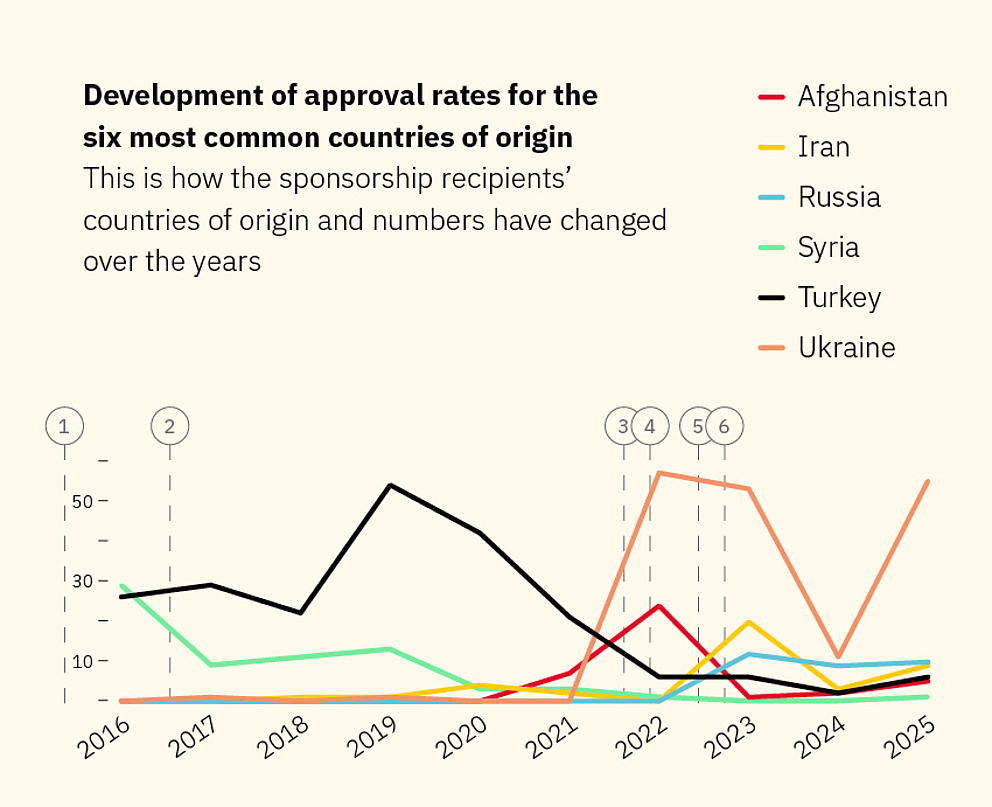

Relevant events during the last ten years (marked in the chart):

1. Syria: The precarious situation in Syria – with civil war since 2011 – as well as in the neighbouring countries where many Syrians had fled, leads to a massive flow of refugees from 2015.

2. Turkey: In July 2016, a putsch attempt fails. The government cracks down hard on suspected opposition figures with mass dismissals and reprisals, including at universities.

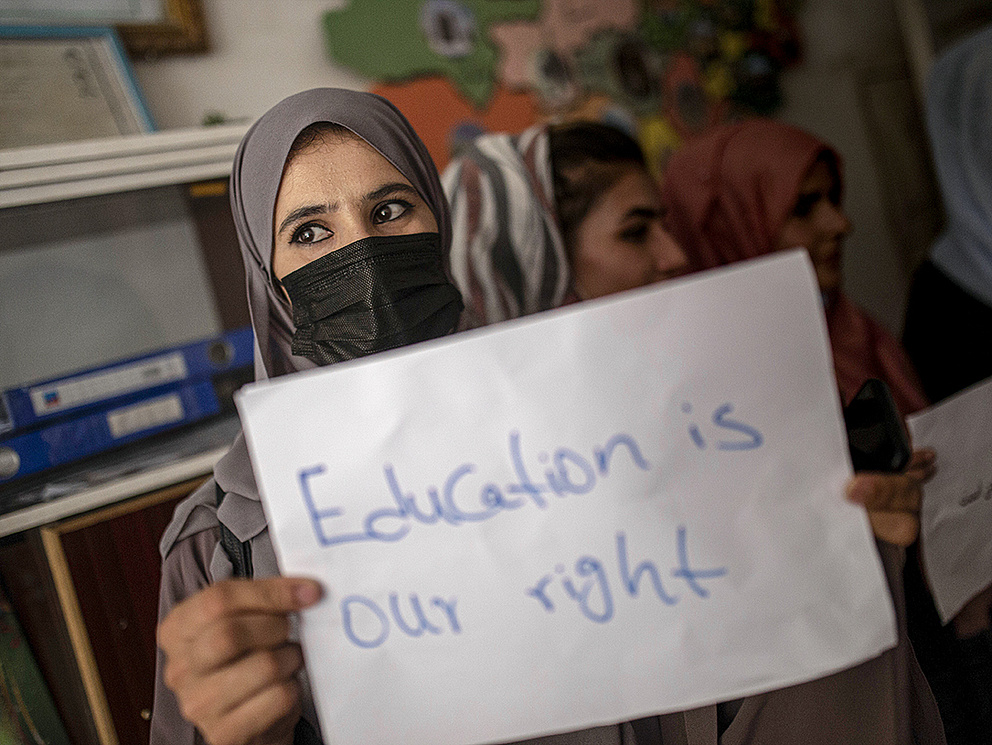

3. Afghanistan: With the withdrawal of US and NATO troops in May 2021, the Taliban initially take power in Kabul and (according to its own figures) by the end of September in all the provinces in the country.

4. Ukraine: On 24 February 2022, Russia starts a war of aggression against Ukraine. The situation had already escalated sharply in 2021, with many Ukrainians fleeing the country.

5. Iran: The death of 22 year old Jina Mahsa Amini on 16 September 2022 as a result of police brutality triggers one of the biggest waves of protest for decades.

6. Russia: Following the invasion of Ukraine, the domestic political situation continues to deteriorate. Russians flee for political reasons or out of fear of being drafted into military service.

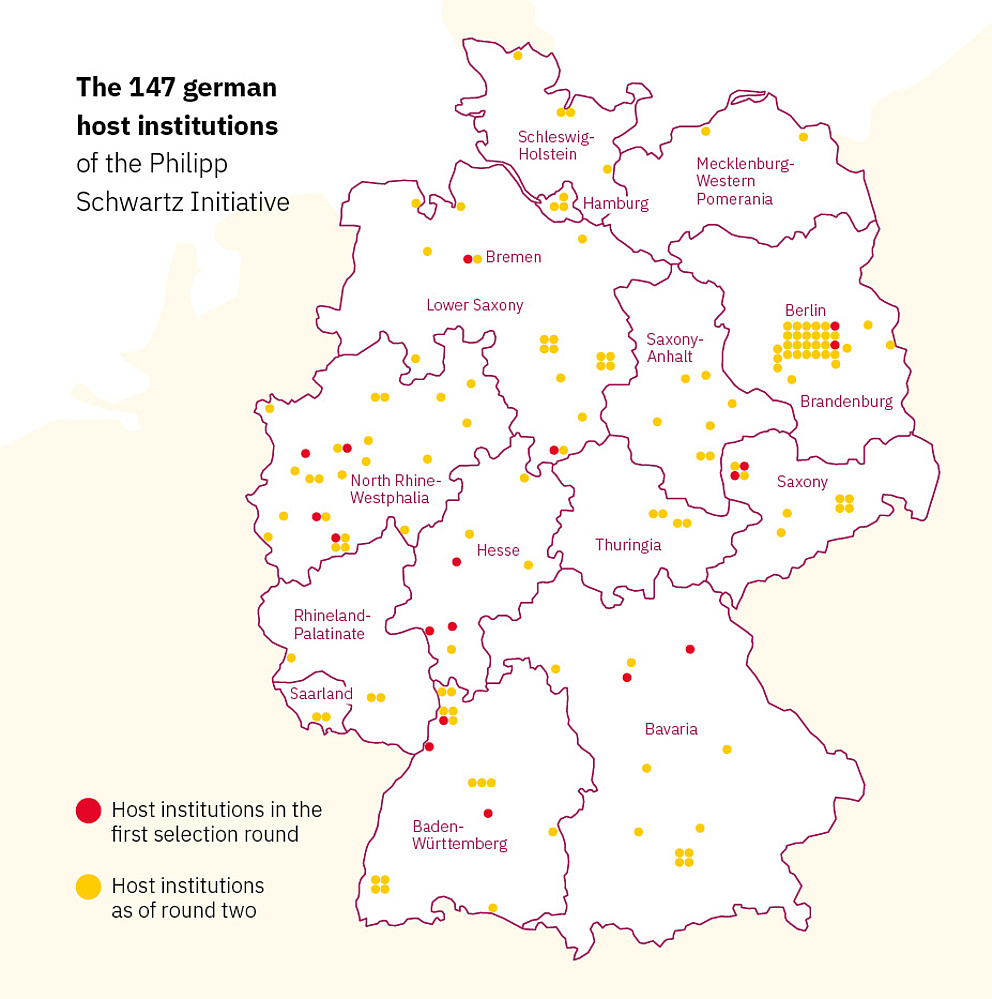

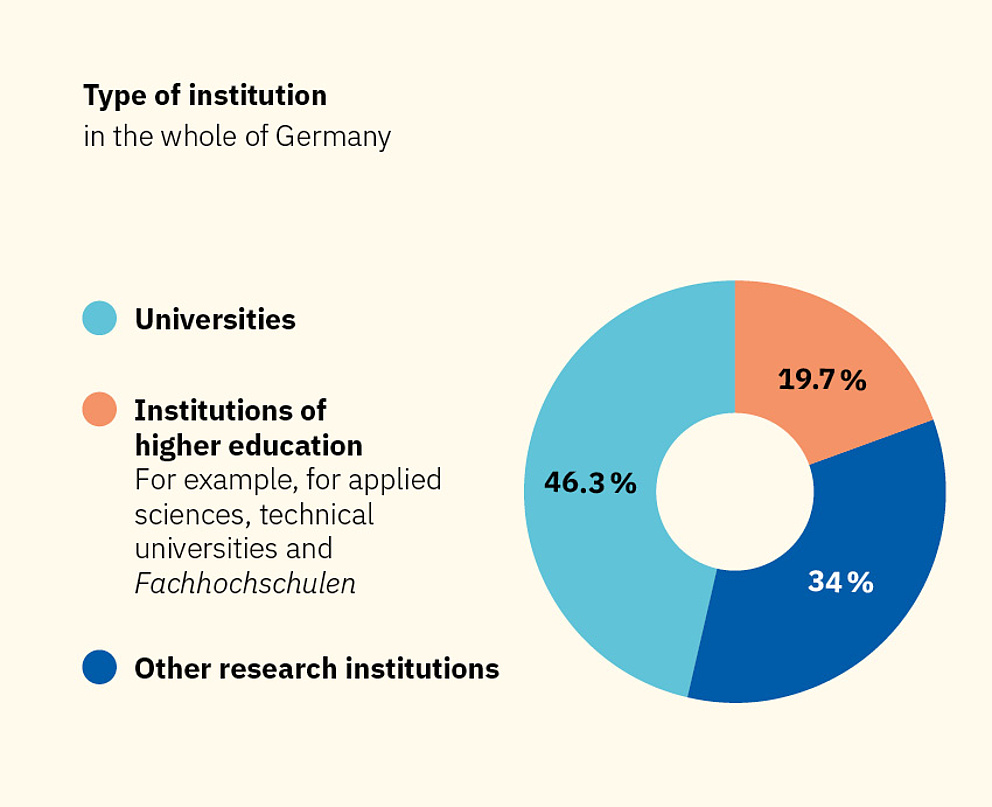

In the meantime, 147 universities have received PSI fellows and built structures and expertise to integrate them to the very best of their ability. For this purpose, as well as the fellowships, the Foundation provides the host institutions with additional funding. Networking is another core building block, so the annual Philipp Schwartz Forum brings together sponsorship recipients, host institutions, mentors, policymakers and international partners. It has now also established itself internationally as a firm format for exchange.

Behind all this is the fundamental conviction that research must be free – worldwide.

Academic freedom – not a reality for many

“Academic freedom is a facet of the right to research and, in the opinion of many experts, of the right to education and freedom of expression, too,” says Katrin Kinzelbach, professor of Human Rights Politics at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg. She is, amongst other things, one of the founders of the highly respected Academic Freedom Index which provides annual data on academic freedom in 179 countries. The figures published for 2024 show that almost half of the world’s population lives in countries where academic freedom is seriously curtailed. And only every third person lives in a country with good to very good protection for the freedom of research.

“Basically, it’s about researchers being able to pursue knowledge according to academic logic and free from governmental and non-governmental pressure,” explains Kinzelbach. From the start, she has been involved in the Philipp Schwartz Initiative and was, for instance, a member of the selection committee. “It’s not only important to protect individual rights but also to respect the autonomy of research institutions.”

“The government exerted enormous pressure. Nobody dared to speak openly anymore.”

Academic freedom is not for granted

In Venezuela after 2014, the biochemist, Jeff Wilkesmann, experienced just what happens when this freedom is removed. “The government exerted enormous pressure. Professors disappeared after voicing criticism. Nobody dared to speak openly anymore,” the PSI alumnus remembers. Colleagues in Germany drew his attention to the programme.

In 2017, he came to TH Mannheim with his two children and his wife, another biochemist who also received the Philipp Schwartz Initiative sponsorship. “The developments in Venezuela opened my eyes,” he says. “The saying that you only know what you’ve had when you lose it really is true. I had previously taken the freedom of research for granted.”

Science in exile, opportunities with the Philipp Schwartz Initiative

The pharmaceutical chemist, Rana Alsalim from Syria, has also been shaped by her experiences. With the aim of helping local pharmaceutical companies to produce desperately needed drugs, she established a working group on cancer medication based on natural substances in Damascus during the civil war. But the interdisciplinary project met bureaucratic hurdles and did not receive any funding. Then bombs fell on the labs.

Alsalim heard about the Philipp Schwartz Initiative from a colleague. Her application went through smoothly. “Due to my qualifications, I was accepted very quickly,” the researcher remembers. Colleagues supported her when she arrived in Berlin in 2017, helped her get accommodation and find her way professionally.

The power of the Syrian diaspora for science and change

The researcher still follows the situation in Syria very closely and with considerable concern. “There is no free research in Syria anymore. That was one of the main reasons why I left the country,” she says. Initially, she hoped things would improve after the regime change but this had not happened so far.

Nowadays, religiously motivated murders were the order of the day, making it impossible for her to return home; Alsalim is a member of the Alawite minority. She has now been made redundant by her Syrian university – due to her religion, she suspects. “This also demonstrates that academic freedom in my country has become a distant prospect, especially for women and minorities.”

“For researchers in exile, academic freedom is the foundation for beginning again.”

From the diaspora, Rana Alsalim draws the public’s attention to this issue. She speaks on panels such as at the 2025 Philipp Schwartz Forum in Berlin where the Foundation brought together Syrian exiles – not least in the hope of having a positive effect on developments in the country by reinforcing the Syrian diaspora. “For researchers in exile, academic freedom is not just an abstract principle,” Alsalim emphasises. “It is the foundation for beginning again, for networking and contributing to global science.”

A fight for recognition

In the course of her Philipp Schwartz Initiative fellowship, Alsalim was initially a postdoc in a medical chemistry group, later moving to industry. She describes her experiences in the German academic system as a fight for recognition. As a foreign woman researcher, she was met with reservations, did not always feel that her performance and qualifications were recognised. “Now, my goals are to get a permanent position in a large pharmaceutical company and a visa for my husband so that he can join me.”

The role of host institutions of the Philipp Schwartz Initiative

Ulrike Freitag has been confronted with biographies like this time and again. The scholar in Islamic studies is the head of the Berlin-based Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO) that has regularly hosted researchers at risk since the inception of the Philipp Schwartz Initiative. “We work on regions like the Middle East, Africa and Central Asia and often see how precarious it can be for researchers there,” says Freitag. “For us it goes without saying that we actively support colleagues who are put under pressure.”

What was important was that candidates fitted ZMO’s research profile and that there were, moreover, realistic career opportunities in Germany. “To become permanently integrated in the German academic employment market at the end of sponsorship is a major challenge,” Freitag reports, drawing on her experience as an academic host and mentor.

65 of them act as mentors for 2 to 6 PSI Fellows. (As of December 2025)

One feature of the Philipp Schwartz Initiative differentiates it from other funding programmes that usually only run for a few months: fellows are supported for up to three years – giving them time to find their feet again and immerse themselves in their research after their exacting experiences. The sponsorship is complemented by additional support measures and the efforts of university administrations which are often highly committed. “We have now actually employed a colleague who helps fellows when they have to go to official appointments or fill in forms and who provides in-depth advice when they are applying for follow-up funding,” Ulrike Freitag explains.

So far, fifty-five percent of Philipp Schwartz Initiative alumni have managed to find a job or acquire follow-up funding – most of them within the German science system, others abroad or in the non-academic sector. Due to continuing poor conditions, returning home is proving to be less viable than was hoped.

When return is not an option

Jeff Wilkesmann for one has given up hope of being able to return home to Venezuela. The danger to himself and his family was simply too great. When his Philipp Schwartz Initiative fellowship came to an end in 2019, he wrote endless applications in Germany. Initially, he worked in science management but in 2024, managed to find a permanent professorial position at Deggendorf Institute of Technology, heading the Bioengineering Transformation Lab whilst his wife conducts research in the lab next door. The Philipp Schwartz Initiative had been a great help on his sometimes difficult journey: “Being a fellow, you are part of a big network and can always ask for advice.”

The Afghan computer scientist Mursal Dawodi is also preparing to live permanently in Germany. She was a junior professor in Kabul specialising in AI-supported translations of the Dari and Pashto languages.

“Women were forbidden to enter the university; my employment contract was declared invalid.”

When the Taliban took power, her career ended abruptly: her employment contract was declared invalid; women were forbidden to enter the university. Since 2024, she has been doing research at Technical University Munich – sponsored by the Philipp Schwartz Initiative. With the aid of machine learning, her project seeks to identify hate speech and misogynistic content in Afghan online texts. “Some people believe my research is directed against my country’s culture and religion,” says Dawodi, who was awarded the medal of honour of the prestigious For Women in Science Award for female researchers in exile in 2023. “But all I want is to be sure that women are safe on the web.”

The Philipp Schwartz Initiative as a bridge to a new life

Starting a new life in Germany proved a challenge for her and her family. “We were psychologically traumatised by our experiences in Afghanistan and had a lot of problems with German bureaucracy,” says the researcher. “Moreover, I had the impression that my new colleagues were way ahead of me. That was very stressful.” One reason for this were their different educational backgrounds: whilst schools and universities in Germany and Europe taught broad general knowledge, girls in Afghanistan seldom learned even rudimentary English.

Dawodi campaigns for greater educational equality through Femstech, a non-profit organisation she founded herself. It promotes digital education for marginalised groups, particularly women in Afghanistan, through online courses in IT, programming, AI and web development as well as through mentoring and coaching.

Mursal Dawodi describes the Philipp Schwartz Initiative sponsorship for her research as a “bridge to a new life” in which she can define her own research agenda. For her, the AI researcher claims, academic freedom was simply vital. “That’s precisely why authoritarian regimes so often fight it.”

Corrective under pressure

Robert Quinn, Executive Director of the international Scholars at Risk Network, says much the same. The organisation, which is headquartered at New York University, has been a close partner since the Philipp Schwartz Initiative was first established. It supports the initiative in areas such as assessing the risks researchers face.

“Academic freedom touches on the question of the kind of society we want to live in,” Quinn emphasises. “Free science searches for truth; its findings help us to make autonomous, good decisions and deal constructively with challenges and diverse opinions.” The knowledge generated in the process was not only a form of guidance but also acted as a social corrective. “Where there is free science, those in power have to face critical questioning. But that is exactly what autocrats want to avoid,” he says. “These people don’t work on the basis of facts, but on the ‘because I say so’ principle – irrespective of whether their words reflect reality or not.”

Development of academic freedom in the USA and Europe

When it comes to academic freedom, until a few years ago, the United States were one of the leading nations. Now Quinn is witnessing at first hand how the political culture of his country has changed enormously – and what this means for the protection of researchers at risk. “In this field, Europe is doing much more and has now overtaken the US in promoting academic freedom,” says the lawyer.

Nevertheless, Europe should not rest on its laurels. Given the political upheavals in parts of Europe, he warns: “The time when we could rely on general declarations of principle and a tradition of governmental restraint is over.” European decision makers should, therefore, enshrine the freedom of research in their countries’ legislation as firmly and as fast as possible.

Academic freedom in Germany – still valued and protected

Taking a look at the latest data from the Academic Freedom Index, the political scientist, Katrin Kinzelbach, notes a slight decline in academic freedom in Germany. Overall, however, it was still very well protected. “But there are no simple recipes for guaranteeing it in perpetuity,” she emphasises. “All freedoms have been won and are thus potentially threatened. We must actively defend them.” To do so, alliances, practices and structures were required – nationally, Europe-wide, internationally. “The Philipp Schwartz Initiative enables us to host colleagues at risk – that is a solidarisation practice.”

Philipp Schwartz Initiative – an appeal for academic freedom and social responsibility

“We have the great good fortune to live in a country that still values and protects academic freedom, even with taxpayers’ money,” says Judith Wellen from the Humboldt Foundation, in summary. The Philipp Schwartz Initiative was itself an expression of this commitment to academic freedom. At the same time, the initiative was also a reminder: “The experiences of fellows like Jeff Wilkesmann, Mursal Dawodi and Rana Alsalim show that academic freedom dies in small steps.” It often happened gradually and initially unnoticed – through abuses, social pressure, self-censorship, thoughts not expressed, posts not published, research ideas not implemented.

“An open society is not a given,” Wellen urges, “it needs our active support every day.” Robert Quinn underscores this social responsibility: “We must do everything in our power to anchor academic freedom as a core value in our culture. We must communicate the fact that a free, self-determined life is founded on free research and a culture of knowledge.”